Surprising black hole discovery changes picture of globular star clusters

An unexpected discovery by an international team of astronomers is forcing scientists to rethink their understanding of the environment in globular star clusters, tight-knit collections containing hundreds of thousands of stars.

The astronomers, including Dr Tom Maccarone from the University of Southampton, used the National Science Foundation's Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA) in New Mexico, USA to study a globular cluster called Messier 22 (M22), a group of stars more than 10,000 light-years from Earth. They hoped to find evidence of a rare type of black hole in the cluster's centre called an intermediate-mass black hole, which is more massive than those larger than the Sun’s mass, but smaller than the supermassive black holes found at the cores of galaxies.

However, they found something very surprising - two smaller black holes, which is unusual because most theorists say there should be at most one black hole in the cluster.

Dr Tom Maccarone, a reader in Astronomy at the University of Southampton, developed the methodology for the study and the surprising result ties in closely to previous research by Tom. He says:

“I had actually suggested several years ago that there were probably black holes lurking among the X-ray sources that had already been seen in globular clusters, and that the one way to pick the black holes sucking gas in, apart from other types of faint X-ray sources, would be to look for the radio emission, but I didn't expect that this particular cluster would be the best place to look. It was still incredibly exciting to see this result and I’m optimistic that we will find more of these objects in other clusters in the future.”

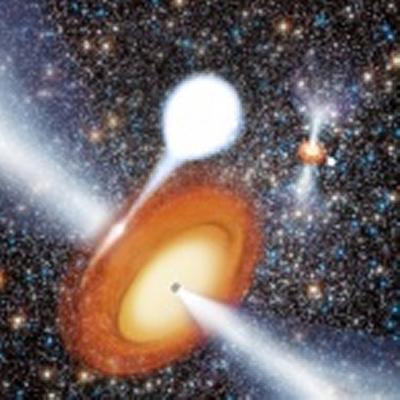

Black holes, concentrations of mass so dense that not even light can escape them, are left over after very massive stars have exploded as supernovae. In a globular cluster, many of these stellar-mass black holes probably were produced early in the cluster's 12-billion-year history as massive stars rapidly passed through their life cycles.

Simulations have indicated that these black holes would fall toward the centre of the cluster and then begin a violent gravitational dance with each other, in which all of them, or perhaps all but a single one, would be thrown completely out of the cluster.

“There is supposed to be only one survivor possible,” says Jay Strader of Michigan State University and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “Finding two black holes, instead of one, in this globular cluster definitely changes the picture,” he says.

The astronomers suggest some possible explanations. First, the black holes themselves may gradually work to puff up the central parts of the cluster, reducing the density and thus the rate at which black holes eject each other through their gravitational dance. Alternatively, the cluster may not be as far along in the process of contracting as previously thought, again reducing the density of the core.

The two black holes discovered with the VLA were the first stellar-mass black holes to be found in any globular cluster in our own Milky Way galaxy, and also are the first found by radio, instead of X-ray, observations. Future VLA observations will help us learn about the ultimate fate of black holes in globular clusters.

Dr Tom Maccarone worked with Laura Chomiuk of Michigan State University and the National Radio Astronomy Observatory; Jay Strader of Michigan State University and the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics; James Miller-Jones of Curtin University in Australia; and Anil Seth of the University of Utah. The scientists published their findings in the latest issue of the scientific journal

Nature

.