"What is essential is invisible to the eye", as Antoine de Saint-Exupery wrote.

This is certainly true for starburst galaxies. Like human beings, galaxies and stars within them are born, they grow and eventually die. Starbursts represent the youthful phase in a galaxy's life. Our Milky Way may instead be considered as a 'middle age' galaxy. So, by studying starbursts, we can effectively peer back into our own Galaxy's past.

These galaxies are real 'baby boomers', creating new, young stars faster than many Milky Way-like galaxies put together. Dusty 'ash' left over by successive generations of stars blocks out much of the starlight, rendering it mostly invisible to the human eye. The bulk of the energy of starbursts emerges instead at longer wavelengths, and one must turn to the infrared in order to understand them.

Now, Japan's Subaru telescope has been used to produce a new view of the most famous of starbursts, Messier 82. Messier 82 is the nearest of such systems, at about 11 million light years from us. Located close to the ladle of the Big Dipper, it is easily visible under dark northern skies to amateur astronomers equipped with a decent pair of binoculars. [1]

Recent observations from space have mapped out a very strong 'super-wind' of dust and gas particles emanating from the starburst. Being ejected at speeds of about half a million miles an hour, this storm sweeps up material from the central regions and deposits it far and wide over the galaxy and beyond. The elements within this material form the seeds for solar systems like our own, and perhaps life as well. The dusty superwind glows brightly in the infrared because it is heated by starlight.

However, all space observatories have size restrictions, which limits the extent to which fine details can be resolved.

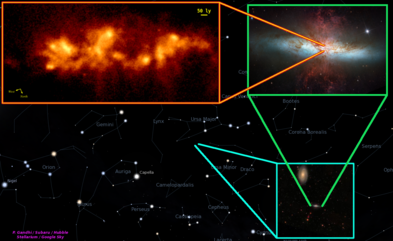

The Subaru telescope, with a large mirror 8 meters in diameter, allows a sharp, magnified view of the core of the galaxy. A sensitive infrared camera called COMICS is attached to the telescope. Together, these give us the capability to capture fine details, equivalent to the ability to see a five yen coin from a distance of 10 kilometers. The final result is an image showing the base of the dusty superwind and young star clusters in glorious detail, better than can be expected from any current or future space mission being planned. [1][2]

The new image bears a striking resemblance a beloved magical creature from the Harry Potter series. [2] But don't be fooled. In fact, it is the action of the superwind and young stars, combined with the tilt of the galaxy away from us, which conspire to carve out the intriguing shapes seen.

The wind is seen to emanate from many sites, rather than any single cluster of stars. We can now see individual 'pillars' of fast moving gas, and even a structure resembling the surface of a 'bubble' about 450 light years wide. COMICS is especially sensitive to the presence of warm dust, which is found to be more than 100 degrees hotter than the bulk of material filling the galaxy. Wide spread, continuous flow of energy from young stars into the galactic expanse is what keeps this dust hot.

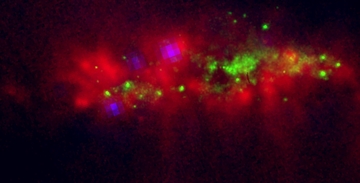

Further insight comes from combining the infrared image with Hubble's near-infrared and Chandra's X-ray data, producing the pretty mosaic shown in [3]. This provides the first opportunity to isolate the infrared properties and hence study the broad spectrum radiation of all kinds of objects spread over the plane of the galaxy, including supernovae, star clusters and black holes. Interestingly, the infrared radiation, which maps out warm gas and dust, appears in regions where the stars do not, meaning that many more stars are likely to be hidden behind the dust.

One exciting question which remains to be answered is whether or not Messier 82 hosts an actively growing supermassive black hole. Detailed analysis of the new infrared data combined with X-rays does not find any such object. But all large galaxies probably contain these monsters, growing and evolving in conjunction with stars. Messier 82 should be no exception, and the search for its big black hole must continue.