Emmissions from shipping

The marine transport sector contributes significantly to air pollution, particularly in coastal areas

Every day, we take around 20,000 breaths so what we can inhale the oxygen we need to survive – without it, we wouldn’t be able to power our cells. But each one of those breaths can also contain substances which have the potential to harm us. Depending on where we are, the air might contain toxic gases and microscopic dust particles which, when inhaled, can cause a number of damaging effects. It has long been known that exposure to air pollution can cause coughing, wheezing, sore eyes, and itchy noses, but it is only recently that we are coming to understand just how many people might be at risk. Recent studies suggest that 5.5 million people per year die prematurely because of air pollution – this is more than 1 in every 10 deaths. There is strong evidence for a link between air pollution and both lung cancer and cardiovascular disease, and growing evidence for effects on asthma and child lung development, and other diseases such as dementia and diabetes. There is also considerable evidence that people with certain pre-existing health conditions are likely to be more susceptible to the effects of air pollution.

Because pollution is a complex mix of gases and particles whose make-up can depend on their source, such as road traffic, fuel burning, ship emissions, and natural processes, we need to understand which chemicals within air pollution are the most important in determining the extent to which our health might be damaged. This will eventually help to increase the efficiency of measures aimed at reducing the effects of pollution, either by targeted reduction of emissions or better monitoring of at-risk groups of people. The component of air pollution most strongly linked to damage to health is particulate matter – microscopic airborne dust particles which are inhaled and deposit in our airways and lungs, and can even enter our bloodstream.

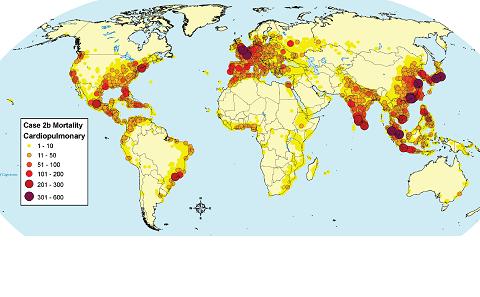

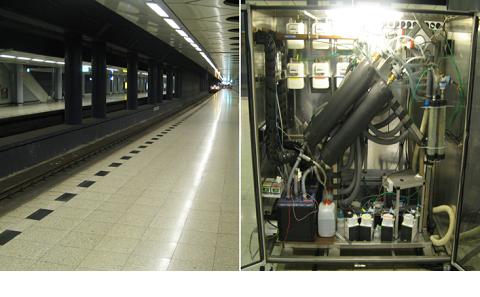

Clean carbon member, Dr Matt Loxham's research has, to date, focused on particulate matter in underground railway systems, in collaboration with Prof Flemming Cassee at the Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu in the Netherlands. Compared to the outdoor environment, this dust is very rich in metals, which are thought to be one of the most toxic components of air pollution. This, combined with the high level of dust underground because of poor ventilation, and the number of people using underground systems regularly, means there is a potential for large numbers of people to be affected. However, he is hoping to use Southampton’s strong links with the maritime and shipping industry to begin to investigate the composition and possible health effects of emissions from ships, which is thought to be a major contributing factor in pollution-related deaths in coastal cities, especially in northern Europe and southeast Asia.

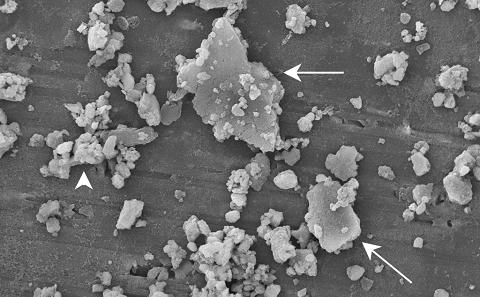

There are a several other questions which remain unanswered, because we don’t fully understand how air pollution causes its effects. How might the effects of exposure over the entirety of life, and even before birth, compare to just a few hours of exposure? What might the effects be on other diseases such as dementia and diabetes? How can we improve the monitoring of people’s exposure to pollution? Answering these questions requires expertise from a wide variety of disciplines. Matt Loxham is supervised by Professor Donna Davies, and currently based in the Faculty of Medicine, where cells from the airway lining can be grown and then exposed to particulate matter samples. This allows the observation of a variety of responses, such as cell death, inflammatory mediator release, and production of antioxidants. Other researchers involved: Prof Martin Palmer, Prof Damon Teagle, and Dr Matt Cooper in Ocean and Earth Science, analyse the chemical composition of the particles, so that their composition can be linked to their effects on cells. Matt has an on-going project with Dr Christopher Woelk, a bioinformatician whose input allows the screening of a huge range of cellular responses to particles which would otherwise be completely unfeasible. He is also working to develop links with statisticians, engineers, and computer scientists so that the questions can be tackled in a more holistic, and ultimately more effective, manner.

The marine transport sector contributes significantly to air pollution, particularly in coastal areas

Underground railway platform with Versatile Aerosol Concentration Enrichment System to collect particles

Scanning electron micrograph of coarse particulate matter (PM10-2.5) collected at an underground railway station.