Turning up the volume on a silent world

Furthering cochlear implant use

For 50 years Helen and Neil Robinson have lived in a silent world. Now the couple is beginning to hear each other for the first time after they both had cochlear implants fitted at the University of Southampton Auditory Implant Service (USAIS).

Not only was it a first for the Service to fit a couple with implants at the same time, but it also highlighted the growing number of deaf people who are coming forward to have the procedure in later life.

Initially thought to only benefit those who had only recently lost their hearing or children in infancy, cochlear implants are now having tangible benefits for people who have been profoundly deaf for decades.

Deaf from birth, the couple have only ever communicated through sign language, lip reading and frustrating attempts to use hearing aids.

Although both were born deaf due to their mothers contracting rubella during pregnancy, the extent to which the cochlear implant will allow them to hear will vary between them and can be difficult to predict before-hand, particularly for people receiving an implant as an adult who have been deaf since birth or early in life.

Shaping future understanding on implant benefits

Exactly how much the pair will eventually be able to hear remains to be seen, but their experiences will help researchers shape future understanding about how the implants can benefit a less developed auditory system.

For now Neil and Helen are enjoying every day noises like boiling a kettle and birdsong. In fact Neil also credits his hearing to potentially saving his life having stepped out of the way of an oncoming car after hearing it before he saw it.

It was Helen who first tabled the idea of having the implant – the invention of which was celebrated on National Cochlear Implant Day on 25 February 2017.

Neil was less convinced, but after two years of consideration he decided to ask his GP for a referral to see if he was suitable.

The couple, who have been married for almost 12 years and have a son, then started on their journey towards hearing. Firstly they underwent surgery to have the implant fitted, which itself carried risks.

Surgeons had to carefully navigate past facial nerves to fit the implant that comprises of two parts, which sit on the inside and outside of the skull just above the ear joined by a magnet.

The inner part of the implant houses electrodes, which receive information sent by the processor on the outside of the skull. When this happens they send pulses of electricity to the brain, which then deciphers them into sounds.

We are very engaged in research and teaching as well as our staff being involved in the training of the next generation of audiologists. It means we also have the opportunity to interact with our patients who may want to help with our research by sharing their experiences

Fine tuning to increase usability

The couple, who live in Wiltshire, will travel to Southampton for a number of follow-up appointments where the devices will be fine-tuned to hopefully increase the range of the sounds they can hear.

Dr Mary Grasmeder, Clinical Scientist (Audiology) joined USAIS in 1996, and has seen the development of their use.

She explained how initially the device was thought to be suitable for those who had recently lost their hearing, who had already developed speech and language skills. Similarly with children, the sooner the implant is fitted the better the outcome would be for them.

Over the past five to 10 years the Service is seeing a rise in referrals from people who have been deaf since birth, but who are still getting significant benefits from the implant.

“Ideally we would be looking for a hearing level of 40 decibels and we would be tuning the implants to be able to ‘hear’ across a range of electrodes which correspond to different frequencies of sound in the environment,” explained Mary.

“People who have been deaf for some time don’t have the same expectation of what sound will be like compared with someone who has just lost their hearing. Because their auditory system is not so well developed it will be more difficult for them to process the information and to understand it.”

The couple are two of the 100 patients that are fitted with an implant each year at the centre. Since it was set up in 1990 over 1,100 people have successfully been fitted with cochlear implants by the Service – the regional centre for the south and the only one of its kind that is based at a university rather than at a hospital.

Engaged in research and teaching

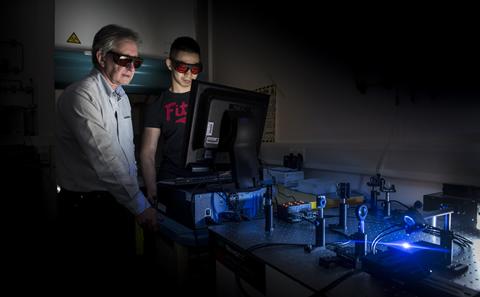

Professor Carl Verschuur, Director of USAIS, explained the University’s unique position. “We are a clinical unit which grew out of the Institute of Sound Vibration Research and because of that we are actually in the university, which is unusual.

“We are very engaged in research and teaching as well as our staff being involved in the training of the next generation of audiologists. It means we also have the opportunity to interact with our patients who may want to help with our research by sharing their experiences.”

The experience of those people who decide to have cochlear implants having been deaf or hearing impaired since birth is not easy to predict, and that has been the basis of new research at the University.

“Because their experience is more varied, we are just beginning to understand how it takes longer to get used to the implants. We are very interested in finding out more about people who have experiences like the Robinsons. Clinical staff can learn a lot from their process and experience,” added Carl.

Other research areas are also being explored include developing long-term life-long care called ‘remote care’ so that people who have had implants ensure they come back to clinic when they need to and not unnecessarily when an issue can be resolved at home.

Researchers are also investigating how to minimise the damage that can be used during the procedure to fit a cochlear implant while also improving and preserving the health of the hearing system.

How cochlear implant users are better able to hear music is also being developed by researchers at the University.

“We are looking at how to ‘code’ music so that it can be enjoyed by people who have cochlear implants. At the moment cochlear implants are not so good at conveying music. That is a real challenge and one that would mean a lot to people I think,” added Carl.

You may also be interested in:

Enjoying music with a cochlear implant

Interdisciplinary Southampton team helps cochlear implant users to appreciate music.

Personalised sensors for medical tests

Paper-based sensor could test for multiple conditions without the need to visit the doctor.

The extraordinary potential of bubble acoustics

Tackling problems as diverse as antimicrobial resistance and explosive detection.