Southampton scientists discover key 'culprits' in major lung cancer study

Lung cancer is the biggest cause of cancer death in the UK, but a study by a team of scientists from the University of Southampton, funded by Cancer Research UK, has discovered a new way to identify patients who are twice as likely to die from the disease.

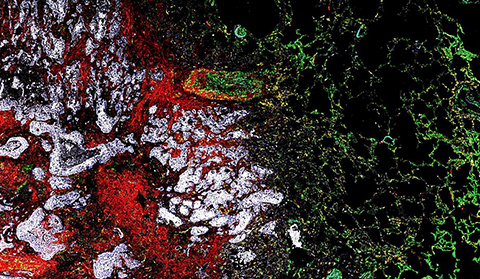

The researchers from the University's Centre for Cancer Immunology used state of the art techniques to learn about a particular type of cell that surrounds tumours - called a fibroblast – in greater detail than ever before. These are healthy cells that support wound healing, but can be hijacked by cancer to help tumours grow and spread.

Using equipment created by University engineers, alongside the very latest technology, they were able to identify three different types of fibroblasts for the first time – one ‘hijacked’ myofibroblast and two ‘normal’ fibroblasts.

The research shows patients with a high proportion of myofibroblasts have double the risk of dying from lung cancer within four years compared to patients with fewer myofibroblasts in their tumours.

Dr Chris Hanley who co-led the research said: “These types of fibroblasts indicate whether a patient is going to survive for a longer or shorter period of time, so this information can potentially be used to give them a more accurate prognosis.

“We also believe that patients who have a high number of myofibroblasts in their tumour could benefit from new treatments that can target this particular cell which would ultimately improve survival rates.”

The team analysed 10,000 fibroblasts from 100 patients, breaking them down one by one using a technique called single cell sequencing.

Using a machine built by engineers at the University of Southampton, scientists were able to capture individual cells into a droplet, before bursting the cell to capture the different molecules. This allowed them to count how many different molecules there are in a given cell, giving it a fingerprint.

This technique revealed the three types of fibroblast, each with its own molecular fingerprint and function. These fingerprints were used to trace the fibroblast’s origins and showed that only myofibroblasts were directly linked to increasing the risk of dying with lung cancer.

Dr Chris Hanley said: “What hasn’t been clear until now is whether all fibroblasts are helpful to cancer, but this work shows that myofibroblasts are the most dangerous culprits. If we can take out myofibroblasts, we have a better chance of taking out lung cancers.”

This is the largest study ever conducted into fibroblasts in lung cancer patients, taking six years to complete. It was the brainchild of Dr Chris Hanley and Professor Gareth Thomas long before the technological advances were in place for them to carry out their research.

Professor Thomas, co-lead said: “We started this idea from scratch when this was a very new technology and it’s been a long haul and an incredible amount of work to get to this point. But the insight that it’s given us provides so many opportunities for future projects and we have a much clearer idea of where we’re going because of this.

“The next step is to develop ways of targeting ‘bad’ fibroblasts to make treatments more effective in high-risk lung cancer patients.”

Dr Iain Foulkes, Executive Director of Research and Innovation at Cancer Research UK, said: “To beat cancer sooner, we need to understand it in detail. Thanks to pioneering research like this, we are moving closer to the day when all patients can receive treatment that is tailored to the features of their tumour.

“The technology available to cancer researchers today gives us unprecedented insights into how cancer starts and grows. We hope that this research will become the basis of new treatments for cancer in the clinic in future.”

The study was funded by both Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council and is published in Nature Communications.