Scientists discover genes that influence risk of fracture and osteoporosis

Scientists at the Medical Research Council (MRC) Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit at the University of Southampton have participated in the largest international study of its kind to identify the genes responsible for osteoporosis.

The study published in Nature Genetics, shows that variants in 56 regions of the genome influence the bone mineral density of individuals. Fourteen of these variants were also found to increase the risk of bone fracture. This is the first time such a large number of genetic variants have been robustly associated with fracture risk.

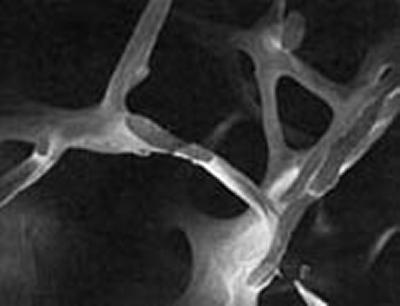

Bone mineral density, measured by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA), is the most widely used measurement to diagnose osteoporosis and to assess the risk of fracture. In general terms high BMD results are found in those with lower risk of fracture. Researchers from the Erasmus University Medical Centre in Rotterdam led the consortium of investigators from more than 50 studies across Europe, North America, East Asia and Australia.

They studied more than 80,000 individuals with DXA scans and examined the relationship with fracture in approximately 30,000 cases and 100,000 controls, in what constitutes the largest genetic study in osteoporosis performed to date.

The 3000 men and women in the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, a collaboration between the University of Southampton and the MRC, provided DNA samples to the study, which were used in a genome-wide investigation to identify genes for osteoporosis and fracture.

Osteoporosis can be a devastating age-related disease: 50% of people who fracture their hip after age 80 years die within 12 months of the event and women older than 65 years are at greater risk from dying after hip fracture than after breast cancer. While the consequences of osteoporosis are well established, the causes of the disease remain elusive. The disease is strongly genetically determined, but the responsible genes were largely unknown, until now.

Professor Cyrus Cooper, Director of the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit at the University of Southampton, says: “This wonderful example of collaborative research between Southampton scientists and a world-leading team has shed light on the critical genetic determinants of osteoporosis and fracture. The findings will lead to the discovery of novel therapies against this common and crippling condition. The analysis included data from the Hertfordshire Cohort Study, a unique population-based cohort study in which early growth, DNA, adult lifestyle, and detailed assessments of bone density and fracture risk have been collected in 3,000 men and women aged 60-75 years. The study has provided critical information on the interaction between genes and the early environment in determining later bone density, bone strength and fracture risk.”

Even though bone mineral density has an imperfect relationship with fracture risk, for example, about 50% of individuals without osteoporosis as diagnosed by DXA still suffer fractures; this study has allowed an unprecedented leap in sheer number of discoveries on human skeletal biology.

Dr Fernando Rivadeneira, assistant professor in Erasmus MC and lead senior author of the study explains: “We have now pinpointed many factors in critical molecular pathways which are candidates for therapeutic applications. Such potential is highlighted by the identification of genes encoding proteins that are currently subject to novel bone medications. This is the case for denosumab (commercial name Prolia), a human monoclonal antibody against RANKL, and a protein mediating the activation of bone resorption. Yet, even more interesting is the identification of several factors that can constitute targets for true bone-building drugs. This is already the case for the sclerostin gene for which an anti-sclerostin antibody is currently being tested in randomized controlled trials.”

Douglas Kiel, Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and the Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife in Boston and senior author co-leading the study, adds: “We also established that, as compared to women carrying the normal range of genetic factors, women with an excess of BMD-decreasing genetic variants had up to 56% higher risk of having osteoporosis and 60% increased risk for all types of fractures. Even more interesting is our discovery of groups of individuals with a smaller number of variants which protected them against developing osteoporosis or sustaining fractures.”