Astronomers see black hole come to life

42 million light years away, 20 million times the mass of the Sun, and coming back to life.

A team of radio astronomers, including Sam Connolly from the University of Southampton, are watching a previously dormant black hole wake up in a dramatic display as material falls on to it for the first time for perhaps millions of years.

Almost every galaxy, including our own, appears to have a black hole at its core. Most of the time these are quiet, with just their invisible gravitational pull shaping their surroundings. But in about 10 per cent of galaxies the central black hole is much more active, swallowing material and spitting out giant jets.

The new study, which is being presented at the National Astronomy Meeting in Llandudno, Wales, shows, for the first time, convincing evidence of the onset, the ‘switching on’ of this active phase, in a black hole at the centre of the galaxy NGC 660 - 42 million light years away in the constellation of Pisces.

In 2012, astronomers noticed that NGC 660 had suddenly become hundreds of times brighter over just a few months. Normal galaxies do not change their brightness very quickly as they are very large systems made of many (relatively) small individual components in the form of stars, gas and dust.

Over the last three years, a team of scientists led by Dr Megan Argo of the Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, has been trawling through archived results from ground- and space-based telescopes. They then used data from three radio observatories: the UK’s e-MERLIN telescope operated from Jodrell Bank, the Westerbork array in the Netherlands and the European VLBI network (EVN), which also includes telescopes in Russia, China and South Africa, that was combined to simulate a much larger instrument – a technique known as interferometry.

Sam’s contribution was to use x-ray astronomy to check the brightness of the source before and after the radio brightening, which helped to rule out potential reasons for the brightening and come to the conclusion that it is most likely to be a newly-awoken supermassive black hole.

Sam says: “As supermassive black holes are so huge, they evolve very slowly, remaining dormant for thousands of years at a time, so to catch one waking up is really incredible.”

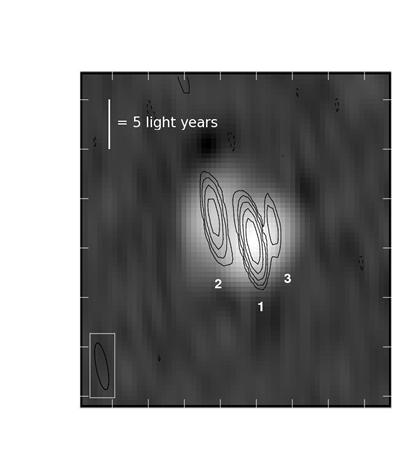

The new images reveal a new, very bright radio source in the very centre of NGC 660, right where the researchers expect to find the central supermassive black hole.

Inactive black holes do not emit large amounts of radiation, so they can only be detected by their gravitational effect on the orbits of stars around them. However, the black hole in NGC 660 is now very obvious, and is many hundreds of times brighter than anything seen in the centre of NGC 660 in the archive of radio images before 2010.

The parallel results from e-MERLIN show that the object is slowly fading, and is similar to other galaxies with more mature systems, and the highest resolution images from the EVN show evidence of a high-speed jet of material leaving the vicinity of the black hole.

Material (gas, dust and stars) near a black hole can sit in stable orbits around the central massive object for a long time, but eventually it loses energy, spirals in, and falls onto the black hole. At the same time, some material is ejected and this seems to have created the outburst and jet now seen in NGC 660.

Studying the jet will give astronomers a clue about the initial eruption of the jet, and how much material fell onto the black hole to cause the outburst in the first place.