First fossil facial tumour discovered in a dwarf duck-billed dinosaur from Transylvania

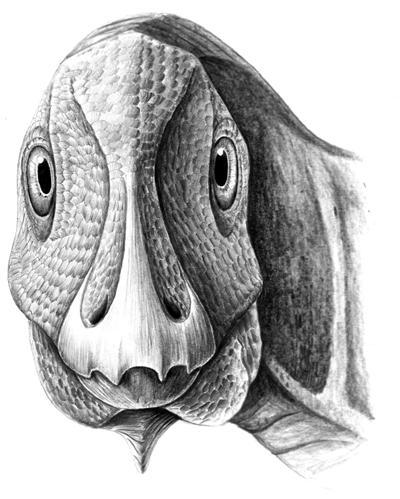

The first-ever record of a tumourous facial swelling found in a fossil has been discovered in the jaw of the dwarf dinosaur Telmatosaurus transsylvanicus, a type of primitive duck-billed dinosaur known as a hadrosaur.

An international group of researchers, including Kate Acheson, a PhD student at the University of Southampton, have documented a type of non-cancerous facial tumour, which is found in humans, mammals and some modern reptiles, but never before encountered in fossil animals.

Kate said: “This discovery is the first ever described in the fossil record and the first to be thoroughly documented in a dwarf dinosaur. Telmatosaurus is known to be close to the root of the duck-billed dinosaur family tree, and the presence of such a deformity early in their evolution provides us with further evidence that the duck-billed dinosaurs were more prone to tumours than other dinosaurs.”

The hadrosaur fossil, estimated to be approximately 69-67 million years old, was discovered in the ‘Valley of the Dinosaurs’ in the Haţeg County Dinosaurs Geopark in Transylvania, western Romania, a UNESCO site.

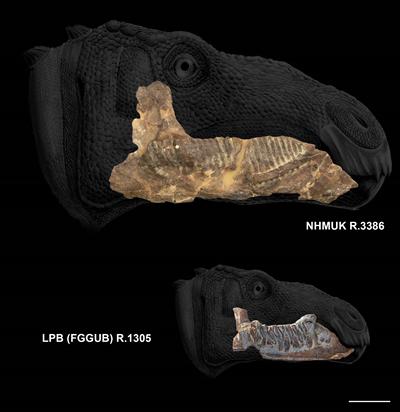

“It was obvious that the fossil was deformed when it was found more than a decade ago but what caused the outgrowth remained unclear until now,” says Dr Zoltán Csiki-Sava of the University of Bucharest, Romania, who led the field trip which uncovered the fossil. “In order to investigate the outgrowth, our team was invited by SCANCO Medical AG in Switzerland to use their Micro-CT scanning facilities and to ‘peek’ un-intrusively inside the peculiar Telmatosaurus jawbone.”

The scans suggested that the dinosaur suffered from a condition known as an ‘ameloblastoma’, a tumourous, benign, non-cancerous growth known to afflict the jaws of humans and other mammals, and indeed some modern reptiles, too.

Dr Bruce Rothschild, from the Northeast Ohio Medical University and a worldwide expert in palaeopathology (the study of ancient diseases and injuries) who studied the Micro-CT scans, said: “The discovery of an ameloblastoma in a duck-billed dinosaur documents that we have more in common with dinosaurs than previously realised. We get the same neoplasias.”

“It was expected, due to the impoverished nature of the fauna, that our project to investigate diseases of the bone in the dwarf dinosaurs of the Haţeg County Dinosaurs Geopark would reveal some interesting results, but the discovery of a rare modern tumoural condition, and one that is so far unique in the fossil record, was a wonderful surprise,” explained Mihai Dumbravă, PhD student at Babeş-Bolyai University in Cluj-Napoca, Romania and lead author of the study, published in the journal Scientific Reports.

It is unlikely that the tumour caused the dinosaur any serious pain during its early stages of development, just as in humans with the same condition, but researchers can tell from its size that this particular dinosaur died before it reached adulthood. Since its preserved remains consist of only the two lower jaws, no one can ascertain its cause of death. The researchers were left wondering, nonetheless, whether the presence of the ameloblastoma could have contributed to its death.

“We know from modern examples that predators often attack a member of the herd that looks a little different or is even slightly disabled by a disease. The tumour in this dinosaur had not developed to its full extent at the moment it died, but it could have indirectly contributed to its early demise,” said Dr Zoltán Csiki-Sava.

“The particular make-up of the rocks allowed us to identify that this fossil was preserved near the channel of an ancient river. In a setting like this, it is extremely rare to find the complete specimen, and so it is almost impossible to determine the specific cause of death. One can only make an informed guess based upon the evidence we have,” added Kate Acheson.

The research involved an international group of researchers from the Babeş-Bolyai University (Romania), the Northeast Ohio Medical University (USA), Johns Hopkins University (USA), the University of Bucharest (Romania) and the University of Southampton (UK). It was made possible thanks to SCANCO Medical AG, CNCS grant PN-II-ID-PCE-2011-3-0381 and POSDRU grant 159/1.5/S/132400 and was also supported by the University of Bucharest, an institution that oversees the management of the Hațeg County Dinosaurs Geopark (member of the UNESCO Global Geoparks Network and of the European Geoparks Network).