Child vaccination levels falling short in large parts of Africa

A study by the University of Southampton shows that several low-and middle-income countries, especially in Africa, need more effective child vaccination strategies to eliminate the threat from vaccine-preventable diseases.

Geographers from the University’s WorldPop group found diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough (pertussis) vaccination levels in Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Mozambique and also in Cambodia, southeast Asia, fall short of the 80 per cent threshold recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO). This means the potential for disease circulation and outbreak in these countries remains high.

Findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

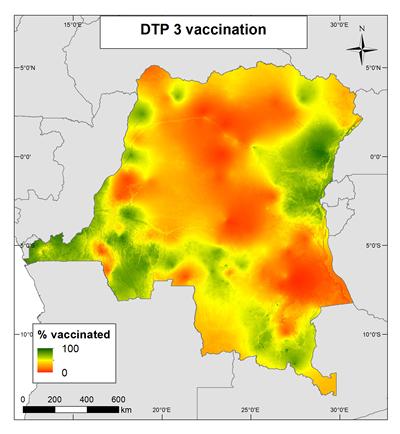

Using data from Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) conducted between 2011 and 2016, the researchers examined the performance of routine immunisation (RI) through the delivery of the three doses of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis (DTP1-3) to children aged five and under, including drop-out rates between doses. They compared this with the delivery of the measles-containing vaccine (MCV), for which additional supplementary immunisation activities (SIAs) are often undertaken. Highly detailed (one km sq.) maps showing levels of vaccine coverage for each country and reflecting the relative performance of routine and supplementary activities were produced.

The maps indicate substantial gaps in the delivery of the first dose of the DTP vaccine, particularly in DRC, Nigeria and Ethiopia – suggesting poor access to routine immunisation. However, where routine delivery of the measles vaccine in the same countries was supported with recurrent SIA campaigns, rates of coverage were substantially higher. In contrast, Mozambique and Cambodia had fewer campaigns and saw no real improvement – although both countries had stronger routine delivery systems.

These results suggest that additional targeted campaigns can make a big difference to immunisation service delivery, especially in areas with poor routine immunisation coverage. Lead researcher Dr Chigozie Edson Utazi comments: “Many things can lead to low vaccination levels, such as poor access to health services, poor education, low stocks of vaccines and even vaccine refusal. We have shown that supplementary activities, as a short-term approach, can help address some of these problems, boost immunisation and improve disease resistance.

“The success of any vaccine delivery strategy lies not only with a good geographical spread, but also in ensuring coverage level among the population is high enough to stop the spread of the disease. We hope our fine spatial scale and regional maps will help countries to understand in greater detail where coverage is low and decide what further interventions are needed in specific areas to work towards disease elimination.”

The researchers now hope to build on their work by extending to other countries and conducting further studies which incorporate data on treatment-seeking behaviour, travel time to health facilities and mobile phone network coverage. It is hoped that this could lead to the design and implementation of tailored vaccination delivery programmes.

The study, supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, also involved scientists from PennState University, Princeton University, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.