Archaeologists find Roman dockworkers diets reflect decline of the Empire

Analysis of plant, animal and human remains from Portus, the maritime port of Imperial Rome, has revealed for the first time the diet of its inhabitants and an apparent shift in food resources as the Roman Empire tipped into decline.

The research, by the universities of Cambridge and Southampton, suggests food was gradually sourced closer to home as Rome’s influence contracted during the 5th century – in particular, its loss of control over North Africa and the major trading route associated with it.

Portus was established in the middle of the first century AD and for well over 400 years was Rome’s gateway to the Mediterranean. It was centred around a large hexagonal basin, which can still be found today near Rome’s Fiumicino airport. The port played a key role in funnelling imports to the citizens of Rome from across the region and beyond; goods such as, foodstuffs, wild animals, marble and luxury items. Portus was vital to the pre-eminence of Rome in the Mediterranean.

In a new study published in Antiquity, an international team of researchers, led by Cambridge and Southampton, reconstruct both the diets and geographic origins of the population of Portus. Their findings suggest that political upheaval had a direct impact on the food stuffs available to those working and living there – specifically, following the ‘sacking’ (or looting) of Rome in AD 455 by the ‘Vandals’ and later the 6th century wars between the Byzantines and Ostrogoths.

Director of the University of Southampton’s Portus Project, Professor Simon Keay, explained: “Our excavations at the centre of the port tell us that by the middle of the 5th century AD, the outer harbour basin was silting up, all of the buildings were enclosed within substantial defensive walls, that the warehouses were used for the burial of the dead rather than for storage, and the volume of trade that passed through the port en route to Rome had contracted dramatically.

“These developments may have been related to the destruction wrought upon Portus and Rome by invading Vandals led by Gaiseric in AD 455, but may also be related to decreasing demand by the City of Rome, whose population had shrunk significantly by this date. These conclusions help us better understand major changes in patterns of production and trade across the Mediterranean that have been detected in recent years.”

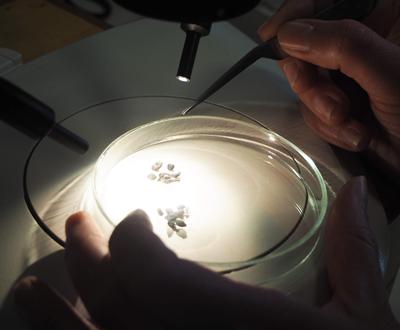

The human remains uncovered at Portus belong to people involved in heavy, manual labour, perhaps the saccarii (porters) who unloaded cargoes from incoming ships. Isotopic (chemical) analysis conducted on remains dating from between the early-2nd to mid-5th centuries AD show these workers had a fairly similar diet to the rich and middle-class people buried at the Isola Sacra cemetery just over a kilometre away. Although there are differences in social status between these people, they both have access to similar food resources. This contradicts what we see elsewhere in the Roman world at this time.

However, later their diet changed, as lead author from the University of Cambridge Dr Tamsin O’Connell explains: “Towards the end of the mid-5th century we see a shift in the diet of the local populations away from one rich in animal protein and imported wheat, olive oil, fish sauce and wine from North Africa, to something more akin to a ‘peasant diet’, made up of mainly plant proteins in things like potages and stews. They’re doing the same kind of manual labour and hard work, but sustained by beans and lentils.

“This is the time period after the sack of the Vandals in AD 455. We’re seeing clear shifts in imported foods and diet over time that tie-in with commercial and political changes following the breakdown of Roman control of the Mediterranean. We are able to observe political effects playing out in supply networks. The politics and the resources both shift at the same time.

“Are food resources and diets shaped by political ruptures?” asks Dr O’Connell. “In the case of Portus, we see that when Rome was rich everybody, from the local elite to the dockworkers, was doing fine nutritionally. Then this big political rupture happens and wheat and other foodstuffs have to come from somewhere else. When Rome is on the decline, the manual labourers, at least, are not doing as well as previously.”