In the UK, low levels of vitamin D are relatively common. While severe deficiency leading to bone disease such as rickets is usually only seen in individuals with darker pigmented skin, researchers at Southampton have found that, in the general population, less marked deficiency during pregnancy may predispose the offspring to osteoporosis and fractured bones when they are adults.

Health risk

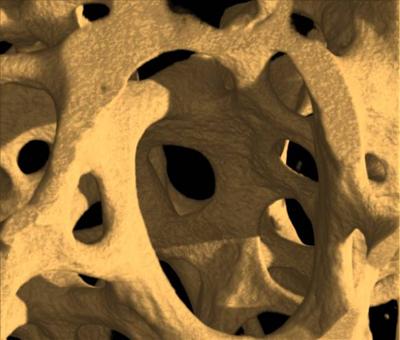

Osteoporosis is a major public health problem costing the UK economy in the region of £2.1bn annually. At 50 years old a woman’s risk of future bone fracture is

50 per cent, while the figure for a 50-year-old man is 20 per cent. “There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that poor growth in the womb and in early childhood might increase the risk of osteoporosis in later life,” explains Dr Nicholas Harvey from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit (LEU) at the University. Nicholas is principal investigator on the Maternal Vitamin D Osteoporosis Study (MAVIDOS), which forms part of a wider programme of research led by Professor Cyrus Cooper, the Director of the MRC LEU, into how factors acting during pregnancy and early childhood might have long-term influences on bone development. “Our particular interest is osteoporosis – previous work from our unit has shown that if you grow poorly in early life, you have an increased risk of weak bones and fracture in adulthood,” says Nicholas.

Vitamin D helps the body absorb calcium from food, in order to ensure optimal calcium mineral content, and thus strength, of the skeleton. In humans, the body can synthesise vitamin D in the skin when sun exposure is adequate and it is also present in a few foods such as oily fish. Since most people’s diets are low in vitamin D in the UK, the majority is derived from sun exposure. Individuals who have darker pigmented skin are at highest risk of symptomatic vitamin D deficiency as the darker skin reduces the ability to synthesise vitamin D; those individuals who are housebound are also at increased risk. Across the general population levels tend to be lower in winter than summer as a result of fewer daylight hours. “Current guidance suggests that repeated short periods outdoors over the summer months should help maintain reasonable levels of vitamin D, but it is difficult to be sure exactly how much you are getting from sunshine exposure,” says Nicholas.

Vital evidence

In previous studies the Southampton team has found several factors which influence offspring bone development in the womb, including maternal smoking, physical activity and nutrition during pregnancy.

These studies have followed the offspring of women into childhood and identified that the most important single factor is the level of maternal vitamin D level during pregnancy. “Children assessed at birth or nine years old born to mothers who have low levels of vitamin D in pregnancy tend to have lower bone mass than children born to mothers who have good levels of vitamin D,” says Nicholas. He explains that as the past studies were observational, they cannot be sure that the low levels of vitamin D in pregnancy actually caused the reduced bone mass in the offspring and therefore MAVIDOS is designed to provide this vital evidence.

MAVIDOS is a clinical trial that was started in September 2008 and aims to recruit almost 1,000 women over three centres – Southampton, Sheffield and Oxford. Funded by Arthritis Research UK, MRC, Bupa Foundation and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), MAVIDOS has recruited over 650 women so far and has recently seen the birth of the 500th baby. “We are delighted with our progress and we are grateful to the women of Southampton for giving up their time to take part in this study,” says Nicholas. “The centres in Oxford and Sheffield will help us look at the different populations in different parts of the country.”

The study’s 500th baby, Rowen Stephen Hall, was born on 18 February 2012. “I think it is really important to do research like this. Nothing is ever going to change without research and we knew it would be perfectly safe,” says his mother Verity Hall. “Hopefully it will help children in the future,” she adds.

Measuring bone mass

Women are recruited at 12 weeks of pregnancy when they attend hospital for their dating scan. If they agree to take part and have vitamin D levels in the low to normal range the women are randomised to either 1,000 units of vitamin D daily or to a matched placebo tablet for the duration of the pregnancy, explains Nicholas. The study tests, in a controlled double-blind setting, whether maternal supplementation with vitamin D during pregnancy will lead to improved bone mass in the offspring.

“The woman takes the tablet every day through pregnancy and the primary outcome is a measurement of the baby’s bone mass – the amount of calcium in the bone – using a bone density scan within the first two weeks after birth,” says Nicholas. “MAVIDOS and other investigations underway at MRC LEU will, we hope, pave the way for potential future strategies aimed at improving childhood bone strength and thus making them less at risk of osteoporosis and broken bones in later life.” Professor Cyrus Cooper, Director of MRC LEU He explains that as well as bone mass data, the team collect information on each woman’s diet and past medical history as well as taking blood and urine samples. They can also look at the babies when they are in the womb using high-resolution ultrasound scanning.

Aiming high

By using ultrasound to study the femur bones of developing babies, the team may gather further evidence that vitamin D can lead to changes in the shape of bones and bone mass of offspring. “In another Southampton study, the Southampton Women’s Survey, we found that if you look at the babies in the wombs of women who have low levels of vitamin D in pregnancy, you find that the baby’s femur is widened at the end, compared to its length – this is a similar shape to femur bones that you see in infants who suffer from rickets,” says Nicholas.

The team hopes that if the study shows that supplementing vitamin D in pregnancy leads to an increase in the bone mass in infants, the evidence will inform government policy on supplementation. “At present government guidance suggests that a low dose of vitamin D should be given in pregnancy and early infancy, but at the moment the evidence underpinning this is limited,” says Nicholas. “This study is likely to be of critical importance in helping the government decide the optimal strategy nationally regarding vitamin D supplementation,” he adds. “MAVIDOS and other investigations

underway at MRC LEU will, we hope, pave the way for potential future strategies aimed at improving childhood bone strength and thus making them less at risk of osteoporosis and broken bones in later life,” says Cyrus. “If MAVIDOS demonstrates that maternal vitamin D supplementation results in optimised bone development of the baby and subsequently the child, it will be the first trial in any area of medicine which clearly demonstrates that a developmental intervention in the mother is associated with an outcome of wide health relevance in the offspring,” he adds. “MAVIDOS also provides a unique opportunity to explore whether vitamin D deficiency actually contributes to illnesses such as diabetes and asthma, and furthermore, whether supplementation with vitamin D will reduce the risk of such diseases occurring,” Nicholas explains.

Other University of Southampton sites

Links to external websites

The University cannot accept responsibility for external websites.