Every year around 12.7 million people across the world are diagnosed with cancer and this number is expected to increase to 21 million by 2030. This following is an interview with Peter Johnson, Professor of Medical Oncology, whose research looks at using the immune system to develop new cancer therapies.

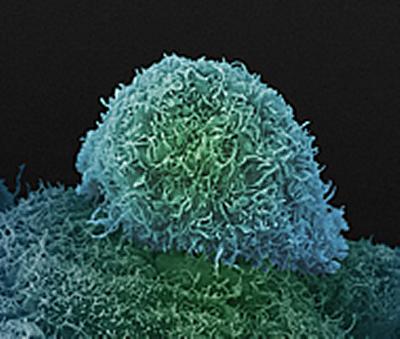

Peter’s research covers two broad areas: in translational research, the application of immunology to cancer treatment through the development of antibodies to modulate the body’s immune system, and in clinical research, the development of better treatments for malignant lymphoma, a type of cancer that has its origins in cells of the immune system itself.

“These areas converge in that we frequently use monoclonal antibodies to treat lymphoma, and indeed they have provided some of the most significant improvements in survival rates in the last decade,” says Peter. “We are now building on this record to use antibodies to target not just the malignant cells of lymphoma but also the normal cells of the immune system, using the antibodies to stimulate or block the control pathways of immunity. This will give us a whole new generation of cancer treatments not just for lymphoma, but many other cancer types as well.”

Peter explains that we are never going to find one treatment that cures all cancers; there are more than 200 different types, all of which need to be tackled in different ways. “The greatest challenge in cancer medicine is its complexity; even within a single cancer there can be multiple sub-cancers that evolve as time goes on, often as a means to evade the effects of treatment,” he adds. “We are only just developing the methods for unravelling all this complexity. The next decade is going to see us grappling with the vast amounts of data that can now be generated to describe cancers at the molecular level. As we do this, we will have to devise ways to spot the weaknesses in cancers and target them for treatment.”

As a clinician, Peter finds the health benefits to patients very rewarding. “There is no better feeling than seeing someone get better as the result of a new type of treatment you have helped to develop; it is what gives us all the energy to keep at the research,” says Peter. “We have a very active clinical trials group in the Experimental Cancer Medicine Centre, with great expertise in translating work directly from the laboratory into clinical testing. The combination of these two strengths puts Southampton in a great position to lead on this work.”