East India Company: insight into the large-scale maritime trade network and the people involved

This project received support through funding from the Careers, Employability and Student Enterprise for a summer internship.

Amber Wood

The voyage of a ship called King George in 1718 includes the statement “this concludes a long and dangerous voyage” [1] providing a glimpse into the perspective of those who had undertaken voyages on behalf of the East India Company. Taken from one of the many journals written to document these voyages, it gives perspective to the amount of time required for international trade, with this voyage occurring between 1718 and 1720, and how it could often prove difficult for the crew. Voyages such as this are recorded and taken from Farrington’s Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs [2] . With these records contributing to a wider project entitled English Merchant Shipping, Trade, and Maritime Communities . The overall aim of this project (The AHRC-Funded ‘Shipping and Maritime Communities, 1588-1765’ project) is to produce a geospatial relational database that displays the scope of maritime communities and the extent of English and foreign shipping during the period.

The East India Company voyages are crucial to this narrative through the large-scale organisation displayed by the company for international maritime trade and its interaction with various maritime communities. Therefore, Farrington’s catalogue is a valuable resource featuring four thousand five hundred and sixty-three voyages representing the significant scale of the operations of this company. This was a result of the monopoly of trade held by the company east of the Cape of Good Hope, which was stipulated in the foundation charter dated to the 31 st of December 1600 [3] . These voyages are recorded because it was “practice for each commander to hand in a fair copy of his journal… to East India House at the end of each voyage”, as Farrington succinctly explains [4] . The existence of these journals allows the study of these voyages and reveals information about the people involved in maritime trade and suggests the scale of operation through the large tonnages of these ships.

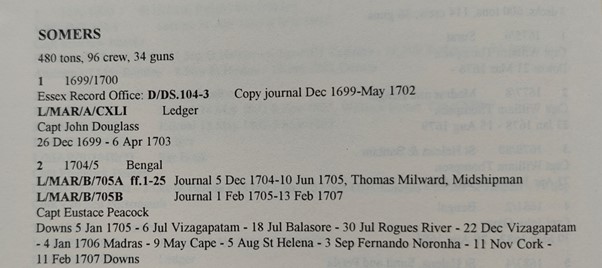

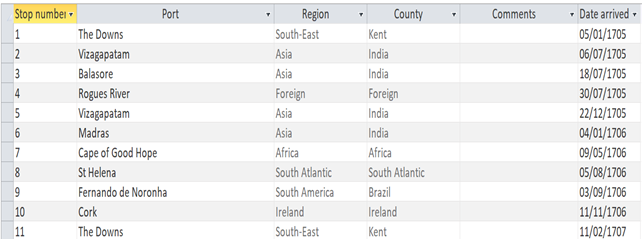

These voyages are displayed on the database to allow public access to these voyages, which detail the captain/s and sometimes crew members involved, as well as each port that certain ships arrived at during its journey. These intermediate ports exemplify the large-scale nature of trade for this company and an example of how they are recorded is shown below:

(Fig 2: example from sourcebook) This entry has the second voyage detailing each port [5] .

(Fig 3: database record of intermediate ports – same example). This corresponds to the database in the intermediate ports tab.

There are similarities between the voyages, with most journeys beginning from the Downs, a well-known port in Kent. The frequency of this port in the records exemplifies the Downs as a major hub of trade and a place of key importance for the company. Furthermore, these ships often visit St Helena, an island that is most famous for Napoleon inhabiting during his exile. Suggesting an important role to this island for the East India’s trade network. Overall, most voyages are undertaken

to India and China, with a few visitations to Japan. There are certain exceptions featured within the journals that are intriguing because of the ambiguous fate of the ships that are stated to have been “not heard of again”. The third voyage of Love is an example of this, with the vessel leaving the Downs during March 1658 and being no longer heard of after its arrival at Madras in February 1659 [6] . Another exception is the frigate Mocha , with the crew becoming pirates after leaving Bombay during 1695 [7] . These are just two examples of the various fates of such ships during these voyages. With ships that end up wrecked or captured on the behalf of the French also featuring in the sourcebook. These voyages that differ from the norm highlight the complexities of maritime trade and the various outcomes that could occur during long-distance travel.

The data Amber entered into the project’s relational database will be used to display geospatial maps of the East Indian Company ships and their voyages, which will be displayed on the project’s website ‘ English Merchant Shipping, Trade, and Maritime Communities .

Bibliography

Images

Wikimedia, in File: An English East Indiaman RMG BHC1011.tiff [accessed 23 July 2024]

Literature

Farrington, Anthony, Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs 1600-1834 (London: The British Library Board, 1999), pp.1-724

__________________________________________________

[1] Farrington, p.363

[2] Farrington, Anthony, Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs 1600-1834 (London: The British Library Board, 1999)

[3] Farrington

[4] Farrington

[5] Farrington, p.412

[6] Farrington, p.457

[7] Farrington, p.612