“An Englishness open to all”

31 March 2017

University of Winchester

Richard Webber, Director, Webber Phillips

This is a corrected transcript of talks given at the ‘An Englishness open to all’ seminar held at the University of Winchester on 31 March 2017. Please do not quote without seeking permission from the speaker.

I would like first of all to thank John for inviting me to this seminar and also for enabling me to access records of some 6,000 survey respondents interviewed by YouGov, whose analysis I will be sharing with you in this contribution to the seminar.

The subject of this talk is the extent to which an analysis of the surnames that people bear can enrich our understanding of the factors that contribute to their sense of identity.

In the first part of this presentation I would like to talk generally about the potential value of surnames as proxies for a person’s cultural background. I will then go on to show how use names have been used in the study of factors contributing to self-identification in the 6,000 respondent YouGov survey.

It is pleasant and not entirely irrelevant to this presentation that I am speaking to you in the English county with which both of my parents identified, one being born in Aldershot and one in Southampton. Having been born myself in Devon I am very conscious that there is an important element of their identity that I have never shared. Our associations with place are much finer geographically than statisticians often appreciate. It is not only when you cross a national barrier than you become an immigrant.

There is indeed a second respect in which today I experience the feelings of an immigrant. It is as a social scientist in the company of other social scientists whose experience of methods of interpreting the world is rather different from my own. The methods that other presenters have used when presenting their findings involve the traditional method of collection and interpretation of survey data. By contrast I am one of a small but growing number of social scientists who rely for our insights on the use of what is called “big data”, not survey data. So, just as immigrants often are, I am sensitive lest the people in whose company I find myself in are people who may harbour some institutional bias against other, less familiar sources of data. As with those who live in Britain with different coloured skin, it is difficult to gauge whether my anxiety is justified or imaginary.

* * * * * * * * * * *

For much of the last ten years my principal interest has been to develop a system which systematically associates people’s names with the places from which they or their forebears originated. One of the reasons why this work is relevant to business and public services is that whereas when we used to meet people face to face the aspect of them that was most apparent was their physical appearance – the colour of their skin, their hair, the shape of their face - when we communicate with people in the digital age it is more likely to be their name that is the most obvious indicator of the identity they are likely to associate with. This is the principal reason why so much personnel recruitment is now name blind. It is also a reason why we should not necessarily accept people’s self-identification as being to the sole relevant measure of their identity. What we imagine them to be is also an important social fact.

One of the benefits of working with names as a proxy for identity is that it enables us to consider how the process of self-identification evolves over a longer historical period than is possible when we are using conventional survey research. Indeed, I would venture to argue that our understanding of the issues that confront contemporary generations of migrants, and the process of their assimilation, can benefit from being informed by our understanding of the outcomes for earlier generations of migrants.

Of the adults who currently live in England some 16% bear Welsh, Scottish or Irish surnames. My mother recounted how as a child in Aldershot she was enjoined never to play with Irish children. I imagine the level of cultural separateness many of Aldershot’s Irish immigrants would have felt a century ago are not that dissimilar to those felt by more today’s immigrant children in Blackburn or Boston. Examining how rapidly and how thoroughly descendants of Irish immigrants a hundred years ago now embrace English values may well give us a useful indication of likely patterns of assimilation or integration of Albanians and Vietnamese.

Let’s look at two examples of how the distribution of names may be relevant to the theme of today’s conference. Where in Britain might you will find the largest and smallest numbers of people of Irish descent? The 2011 census identified Middlesbrough as England’s major urban area with the smallest proportion of people who self-identify as Irish. Yet when urban centres are ranked by proportion of

people with Irish surnames Middlesbrough is the highest. Middlesbrough was a favoured destination for Irish immigrant 150 years ago. Few have followed in their ancestors’ footsteps during the last fifty years.

What relevance does this have to social research? A good example comes from the analysis of support for devolution during the Scottish referendum campaign. Using YouGov data we find very different attitudes towards independence between respondents in Scotland who have surnames which originated in Scotland from those Scots respondents whose surnames originated in Ireland. Respondents with Irish surnames were hugely more supportive of Scottish independence. Our hypothesis is that many of them retained the antipathy towards the English establishment that had developed among their forebears when living in Ireland, an antipathy that was far less evident in the Scots who, other than in Highlands, had no collective experience of similar historic grievances.

Interestingly the group which was by far most hostile to independence were respondents living in England but with surnames originating in Scotland. It is not difficult to understand the reason.

In this context it is relevant to note that to the 60,000 capacity of Parkhead, Glasgow Celtic’s stadium, far exceeds the number of Scots describing themselves as Irish in the 2011 census. Self-reporting as Scottish is not inconsistent with retaining the tribal behaviours that mark you out as an Irish Catholic.

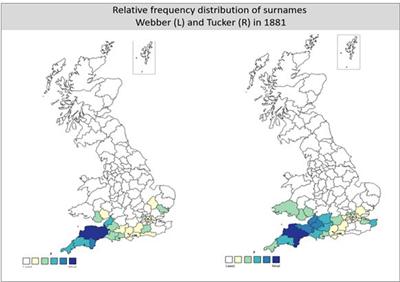

I hope these examples from Middlesbrough and Glasgow help to explain our rationale for analysing the YouGov survey data using respondents’ surnames as a proxy for ancestry. To this end we have appended to each respondent record an additional field indicating whether their name suggests English, Welsh, Scottish or Irish descent. Where respondents bear non-white British surnames, we have flagged them too. Most people can identify whether a name is white British or foreign. But most people, particularly those who have left home to go to university, underappreciate how regionalised many English surnames are. Though my parents came from Hampshire, I was born in Devon, which with Somerset is the heartland of my surname as can be seen from figure one which shows the national distribution of the names Webber and Tucker in 1881. In areas marked in blue on the map the proportions are 30 times greater than in Newcastle upon Tyne. Even common occupational names such as Smith and Taylor continue to show quite distinct regional variations.

Figure one

To make use of this information to understand historical migration patterns we use a national database of surnames to identify the postal area (for example SO for Southampton) with the highest concentration of each surname with over 100 occurrences nationwide and hence the part of the country in which present residents’ ancestors are most likely to have originated some 500 years ago. Taking people bearing the names Webber and Tucker for example, we can safely infer from surname maps that there has been a significant migration across the Bristol Channel from Devon and Somerset to South Wales. Until recently many of the descendants of these migrants continued to support the Devon Societies that sprung up in many of the larger towns in South Wales.

Figure two

In the context of the current discussion about the “Somewheres” it is worth noting how figure two reveals that there are regions of the country which have particularly high proportion of people whose names are indigenous to the local area. Examples are the Potteries, the Black Country, Cornwall and Norfolk, all regions which avoided large scale migration from other parts of England as well as from abroad. It may not be an accident that these regions have proved fertile territory for right wing politicians. Regions of the South East where right wing parties have achieved less purchase tend to be ones with a very high proportion of non-local English names.

* * * * * * * * * * *

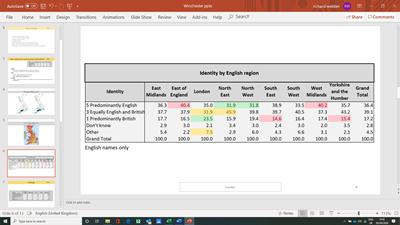

Turning now to the analysis of the YouGov survey data our first analysis looks at regional variations in respondents’ attitudes towards whether they felt British and English. As John has already explained each respondent is placed into one of five different grades. It surprised both of us how few respondents didn’t actually feel some degree of Englishness and how little attitudes vary by region, see table one. In this respect London is not as dissimilar to the country as many people may imagine. The interesting feature of the London data is its level of polarisation. It has the fewest respondents who are in the middle category - most feel one way or the other. I suspect we would have seen much greater divergence from the national average had we been able to separate respondents from inner London from those in outer London.

Table one

The next stage in our analysis was to separate out respondents who had English surnames who lived in the region in which their surname originated from and those that lived elsewhere. Our hypothesis was that people whose ancestors had lived in the areas for very many generations would have a greater feeling of Englishness than people whose ancestors had moved to a different part of the country. Would we find that the people whose ancestors had not moved region were more local in their orientation and hence relatively more likely to identify with being English?

This hypothesis was not supported by the evidence in table one, the difference being relatively small. Some of this difference is probably attributable to differences in the social class and education or more mobile people, with better educated people being more likely to move regions and being more likely to move to London. Were we to strip out these effects it is doubtful whether living in the English region of your ancestors would have any bearing on your identity, not what we imagined.

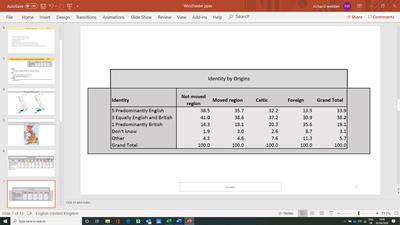

Table two

What proved more revealing was the attitudes of English residents with surnames originating in Scotland, Ireland and Wales. Many of these are less likely to be first generation migrants as descendants of the big waves who migrated during late Victorian and Edwardian years. The most striking feature of this group is the greater than average extent to which Irish people self-identified as Other. This seems consistent with the results of the analysis of opinion during the Scottish referendum campaign, with people of Irish ancestry not feeling Irish enough to identify themselves as Irish but not feeling sufficiently English to identify as English either.

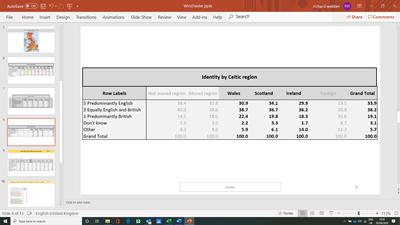

Table three

The experience of Irish immigrants to England is somewhat different from that of the Scots and of the Welsh. Whilst it was often the impoverished Irish who migrated to manual work in England, a much higher proportion of Scots who migrated to England were well educated, the less well-educated choosing to emigrate to the colonies. Indicative of these differences is that when one examines the surnames of Members of Parliament in 1945, the overwhelming majority of Members with Irish surnames sat on the Labour benches, as did those with Jewish names, whilst Members with Scottish names, Macmillan and MacLeod being examples, were equally divided between the Conservatives and Labour despite the latter’s large majority. Overall English people with Scottish names were the most likely of immigrant groups to feel English.

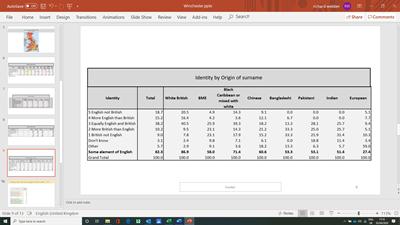

Next we looked at the identification of respondents from outside the British Isles (table four). The pattern here is that overall the Black and Minority Ethnic population is far more disposed that the white British population to feel British rather than English, the exception being the Black Caribbean population. Variations in balance between British and English identification align very closely both with the propensity of minority groups to live in segregated neighbourhoods and their likeliness to co-habit with white British partners.

Table four

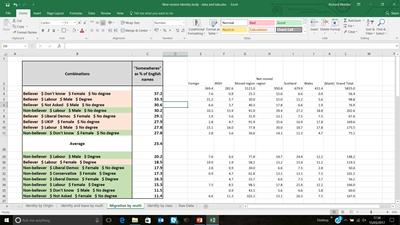

Our final analysis provides interesting evidence of there being combinations of factors which contribute to the identification with Englishness as that these factors do not necessarily combine in the linear manner that can often be supposed when models are being built. In this table “somewhere” indicates the difference in the percentage of respondents self-identifying as “English not British” over those claiming to be “British not English”. The differences are calculated only for respondents living in the same region as their ancestors and whose names are English.

Each row indicates a permutation based on whether or not they are a religious believer, how they would vote, their gender and their level of education. Most of the largest “somewhere” majorities are in permutations including religious believers and people without degree. Interesting exceptions are Labour supporting females with degrees, even if they are believers, who tend not to be “somewheres” and Labour males with no degree even if they are non-believers, who fall into the “somewhere” grouping.

Table five

In summary then I would put to you that there are many different factors that contribute to people’s sense of identity and that many of them combine in ways which are not necessarily the sum of their individual elements. Ancestry, geography and neighbourhood are all important contributors - identities are as much the product of historical experiences and present day social interactions as they are of individual characteristics.