American universities are used to not being supported by their government

How Trump is cracking down on science in the United States

The United States has been leading scientific research worldwide for decades. According to the Times Higher Education 2018 University Ranking, 6 out of the top 10 Universities in the world are American. Having just had an opportunity, to spend a month in the United States in the framework of the German Marshall Fellowship, I have seen first-hand how Trump’s election is affecting science in the US. Just this week, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Administrator Scott Pruitt announced that the EPA will bar scientists who have won agency-awarded grants in the past from serving on its independent advisory boards. Critics say this could open the way to more industry-friendly advisors on the panels, which provide the scientific input for agency decisions around pollution and climate change regulation.

The arrival of President Trump in the White House has brought along an administration that is hostile towards science and is happy to disregard or tweak facts for political gains. The crackdown on science ranges from removing ‘climate change’ from Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) grants, faking science to justify the recent proposal to restrict access to birth control, to deleting hundreds of data sets and scientific reports from governmental websites.

The Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), founded in 1969 by scientists and students at the MIT, has been at the forefront of monitoring the Trump administration’s crackdown on science and supporting researchers across government and academia. The Centre for Science and Democracy at UCS is acting as a watchdog. It’s ‘Attacks on Science’ database lists cases of disappearing data, silenced scientists, and other assaults on scientific integrity and science-based policy.

While many are hoping that the Trump administration will be replaced by a more science-friendly government in 2020, Trump’s policies could have a long term effect on US leadership in science. Similarly to Brexit Britain, US universities are reporting declines in enrolment of international students and staff. The negative narrative around science and increasingly restrictive immigration policies are to blame for that. Funding cuts to the US science budget (with the exception of NASA), alongside scientific advisory bodies waiting to be appointed, could also have long term effects on US leadership in science.

That being said, my trip to the US also gave me hope. Hope in the resilience of US institutions and its scientific community. The new administration caused a paradigm shift in US academia: from whether scientists should engage with non-academic audiences to how they should engage. While previously, researchers were often reticent to engage with the public, the media and policymakers, the post-fact politics that characterise the US government today do not allow scientists to withdraw to their ivory tower. They need to fight back and have done so in several ways.

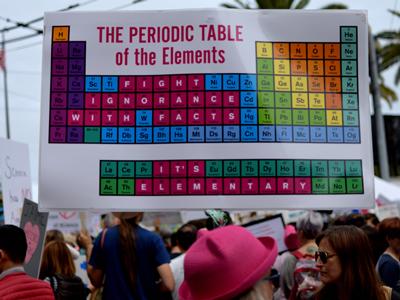

On April 22, 1 million people participated in the March for Science across the US and the world. Particular issues of science policy raised by the marchers included support for evidence-based policymaking, as well as support for government funding for scientific research, government transparency, and government acceptance of the scientific consensus on climate change and evolution. The march is part of growing political activity by American scientists that has also led to scientists deciding to run for office. A newly formed group called 314 Action is supporting scientists who want to run in elections. It’s the science version of Emily’s List, which focuses on pro-choice female candidates, or VoteVets, which backs war veterans. Other organisations such as Science Debate raise scientific issues during election debates and hold candidates and elected officials accountable.

Public and private institutions such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) are stepping up efforts to compensate for cutbacks elsewhere. Critically, the US being a federal country, this administration’s negative effects are mitigated by State legislatures, governors and mayors across the country. Similarly, the United States have a history of US universities being very independent from the federal government. We are already seeing how cities and states are committing to continue implementing the Paris Agreement. And, as I was told by several colleagues in the US ‘American universities are used to not being supported by their government’. Paradoxically, in the current situation, that might be their biggest strength.

Julie Cantalou

Public Policy|Southampton

@JulieCantalou