CARTOGRAPHIC OPERATIONS ON LEVEL 4 Event

- Date:

- 20 February 2017 - 20 March 2017

- Venue:

- Level 4 Gallery, Hartley Library

For more information regarding this event, please email Professor Jussi Parikka at J.Parikka@soton.ac.uk .

Event details

A new exhibition in Southampton on mapping opens on 20 February. ‘Cartographic Operations’ will sit alongside the exhibition in the Special Collections Gallery (Hartley Library), ‘Beyond Cartography: Safeguarding Historic Maps and Plans’, and there will be a joint Private View on Tuesday 28 February, 5pm to 8pm. The exhibition is organized in conjunction with AMT and features AMT affiliated artists.

About the show:

In Bernhard Siegert’s ‘The map is the territory’, he refers to the idea of ‘cartographic operations’. The suggestion is that our way of seeing the world is not simply represented in maps, but that map-making is itself a play of competing signs and discourses producing our subjecthood. These are the coordinates we come to live by, which in turn influence the marks and signs at our disposal when we seek to make and share representations of the world.

This exhibition brings together three alternative cartographic operations.

Jane Birkin’s 1:1 is a direct mapping of infrastructure behind the white space of display. It is a piece produced by performative procedure: a regulated operation where authorial control is established at the outset and rules are strictly followed. Electric current and metal are plotted using a DIY store metal/voltage detector and the information transferred simply to print.

There are literary precedents for mapping at this scale. In Jorge Luis Borges’s short story On Exactitude in Science cartography became exactingly precise, producing a map that has the same scale as its territory. And, in Lewis Carroll’s Sylvie and Bruno Concluded, a German professor tells how map-makers experimented with the use of ever larger maps, until they finally produced a map of the scale of 1:1. ‘It has never been spread out, yet’, said the professor. ‘The farmers objected: they said it would cover the whole country, and shut out the sunlight!’ In this case, the gallery wall is covered, shut off from light and eyes. Although 1:1 is an impassive engagement with the rule-based activity of cartography, it simultaneously performs an affective act of display.

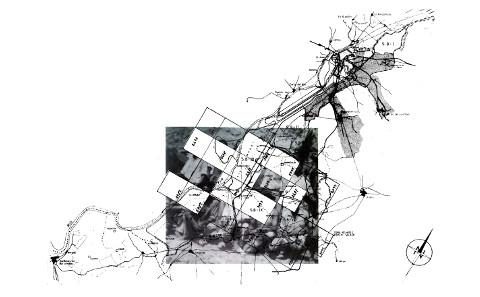

Abelardo Gil-Fournier’s Marching Ants draws upon historical photographic sources of landscape transformations driven by the building of large water irrigation infrastructures as part of 20th century Spanish land reforms. The work is a reminder of the use of forced labor to transform the lines of maps and diagrams into tunnels and channels in the earth. An economic exploitation of political repression that took place during more that 20 years within Penal Colonies that have been since then removed and forgotten.

The marching ants effect, also known as marquee selection, is the animated border of dashed lines often used in computer graphics programs where the dashes seem to move slowly sideways and up and down, as ants marching in line. It is the visible sign of a potentially immediate transformation within the surface of the screened image. Considered from the point of view of an aerial landscape, operations such as gridding, ordering or leveling land, the marching ants are a form of cultural technique, the tracing of an interaction between imaging technologies, environment, geography and governmental knowledge

Sunil Manghani and Ian Dawson’s Not on the Map is an image-text installation built into the gallery space. It draws upon maps held in the University’s Special Collections, picking out details from a volume of Spanish maps from the Ward Collection and military maps of Portugal taken from the Bremner Collection. These details are placed in dialogue with tracings from early and recent figurative works by Jenny Saville – the noted contemporary British artist associated with the Young British Artists of the 1990s and well-known for her large-scale female nudes. The rendering of her work here offers a play on the distinctions between perception/sensations and geography/landscape, which combined with details from real maps only blurs and disorientates our ways of reading lines, sites and points of view. In recent work, Saville shows bodies together, such as an infant wrestling in a mother’s arms, couples embracing, a fight, and children playing in the sand. Such scenes take us into uncharted territories, which we might liken to the enigmatic inks of long forgotten maps. Unlike the spectacle of the body in Saville’s early work, the configuration of images staged here pose as private, idiosyncratic landscapes made up of no single definite lines.