In October 2023, my team won an award we’ve had our eyes on for quite a while. It was the insights empathy award, which recognises advancements in audience research and its application in designing products and services.

This meant a lot to us, because a few years ago user research and design insights were not used to drive strategic outcomes at our university. Following our latest win, I was asked by a number of people from inside and outside the higher education sector to explain how we managed to establish user research and other human-centred functions more widely, given the cultural challenges often encountered at universities. I was also asked about the difference it made over time.

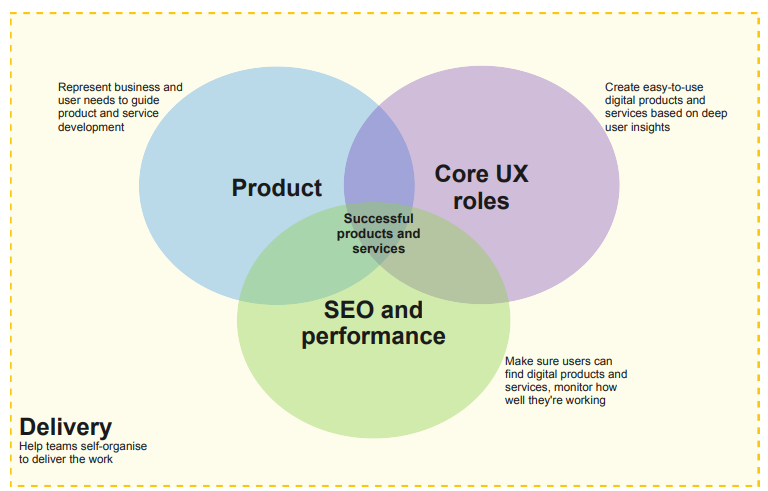

For context, I work at the University of Southampton (UoS) where I head the Digital User Experience function. It includes human-centred design disciplines (content design, UX and interaction design, user research) as well as performance, product and delivery disciplines.

Diagram 1: our disciplines work together

Like many other higher education institutions, Southampton is a complex organisation, with strategic objectives that span research, education, and enterprise. It is also a Russell Group university, research intensive university and while it is gazing towards the future, it also embraces its heritage, which occasionally provides an interesting viewpoint when looking at generating a change.

None of what I am going to describe here was easy (sorry, not sorry 😂). I view it with a philosophical lens: it is an evolutionary process rather than a revolutionary one. It is a journey through an ever-changing landscape that has no end because complex organisations have complex ecosystems that require careful navigation over time, and nothing ever stays the same.

This blog post is about some steps and lessons learned along the way if you are thinking of setting up user research and design disciplines in your organisation.

Lesson 1: genuine commitment to learning supported by a vision

Learning about people who use your products and services is an organisational commitment. The same applies to putting frameworks in place that allow teams to succeed.

As a starting point and beautifully coined by Erika Hall: “If your organization isn’t prepared to learn, it doesn’t matter how much research you do”.

In 2019, we embarked on our digital transformation journey and the OneWeb programme was born. There were two key principles at its core: adoption of a human-centred approach, and agile working practices. The mandate was to find the overlapping value between what the University requires and what the end-user needs, starting with the website. Fundamentally, the OneWeb programme was about investing to achieve defined target outcomes.

In reality, an organisation needs to buy results and it accesses those results by implementing the practice. In this case, it is human or user-based research and design. In order to learn about the people who visit our website, we had to take on the first step towards building empathy. Empathy starts with user research…

As many of you know, user research gives you the opportunity to speak to, observe, and/or hear from your target audiences, giving you first-hand insight into who they are, the problems they encounter, and what they might need from the product you’re designing.

It’s fair to say that at the time, and even occasionally now years later, there is still a fundamental misunderstanding about user research, what it is, how long it takes and why you should do it (but let’s not digress – this is a whole topic for another blog post!). Luckily for me, at the time, the organisation was prepared to buy the results of this approach at scale, even though it perhaps didn’t fully understand the methodology itself.

My team researched, investigated and designed a lot of core services with end users, involving hundreds of stakeholders along the way. What we discovered and validated is different audiences’ needs and how they’re linked to one another from an end user’s unique perspective. This is the underpinning blueprint to the journeys people want to take, which in return help meet university objectives. Win-win.

The key lesson is that user research and human-centred disciplines do not happen in vacuum. You need to get commitment from the top, mandate to operate in this way and understand the competitive advantage it can serve the wider organisation longer-term. In all honesty, mandate and commitment has wavered at times, and this is why it is clear to me how vital it is for delivering useful results. There has to be a strategic intent as it needs hooking directly to a strategy, policy and standards, or at the very minimum – have agreements in place. And in order to deliver return on investment, you need some clear targets or well-defined benefits you are going to achieve by implementing the practice.

Lesson 2: pairing team members with experienced practitioners

When you secure commitments, knowledge transfer is the next important component of our ways of working. Initially we invested in bringing in experienced user researchers, content designers and other professionals who paired with members of the team or interns that learned the ropes, methodology and were able to put their knowledge into practice. I also looked internally where I could find talent, such as career services or working directly with the heads of schools in academic areas of related disciplines, for example, psychology, software engineering, languages, game design to name but a few.

In the background I worked with my new friends in Human Resources (HR) and finance on setting up disciplines that were brand new to the organisation, including user research, UX and interaction design, as well as budgets to fund these roles.

On a practical level this meant creating discipline pathways, getting job descriptions written, and getting them graded via panels. All of it had to be done quickly because of annual budgets, plus it’s hard to go to market and find people that were skilled to get the job done. This was a huge undertaking and a challenge especially when the pandemic hit the world.

Recruitment is always rather challenging due to market conditions. At that time, it meant salaries were high, the market favoured contract jobs rather than permanent roles and skilled people were in shortage.

It was a risk to what we might be able to deliver in the programme’s timeframes because your budget can only go so far and there was a lot to do. Also, the organisation will only have a certain amount of patience for the benefits it’s waiting for and this is not always something that is easy to gauge.

My strategy for recruitment was always about ‘growing my own (talent)’. It was also about spotting existing talent in people who might not have had the opportunity to work in a particular field but demonstrated transferable skills and a healthy attitude to learning. In some places I took calculated risks by appealing to potential prospects in different ways. Money and job security is important as basic hygiene conditions, but equally important is the culture and type of work you build in teams.

I strongly believe that if you adhere to these core principles, you are likely to yield results and build an organisational competency longer-term that many overlook in support of short-term gains. We had some great successes with internships, something that I am keen to carry on and develop further. I believe that it’s important to give people opportunities as it’s hard to get a break in these disciplines.Taking the principle of knowledge transfer from OneWeb, finding talent that would want to learn and pursue this as a career path, develop them in-house ‘on the job’ was, and still is, the key game in town. This was fundamental to not only the user research discipline, but also to others.

My advice is to get clear on what you really want to accomplish with disciplines’ time and skills, articulate clearly what kind of team culture you are looking to build and encourage people with similar ethos to apply for jobs. You also need patience, drive and tenacity to see your vision through.

Oh – and make friends with your HR and Finance colleagues because that will determine how quickly you are able to get wonderful people embedded in your team!

Lesson 3: setting up teams for success

This is where your promise needs to live up to expectations you’ve set. It’s also where frameworks, tools and processes come into their own. Research Operations (ResearchOps) is so much more than just getting in user researchers. It is about a shift in mindset across all disciplines and training everyone from the ground up.

To start with, when recruiting or developing our team culture, everyone has to care about the people who are using our services. A culture of empathy is needed to ensure we translate various points of views around common grounds. We need to enable a two-way street with our users and the organisation so we build a shared appreciation. Basically, empathy is the bridge, and let’s face it – there isn’t enough of it in the world, so I think it is a pretty good idea! It is also about opening our work and methodology to others, including colleagues from the organisation. By doing so, our research, insights and designs are more likely to get accepted in the first place.

Some of the processes, stepping stones and measures that we put in place were a combination of informal and formal elements such as:

- Firstly, setting up heads of disciplines was fundamental and it has two aspects to it. There is an organisational element recognising the need and value (following the transformation programme) and an adoption process. The second part to it is more to do with ‘getting our house in order’ as part of the team. This is important because any leads or heads of discipline will bring their own perspectives and will want to improve how we do things as a discipline and collectively. You need solid foundations for things to work well.

- Documentation of the user needs and making sure these are mapped to journey and performance measures. This is where we use different disciplines to work together and get the best of all worlds: user researchers and performance analysts can be best friends! While performance describes the ‘what’ pretty well, it has a much bigger value when the ‘why’ is explained via qualitative insights. It’s that corroboration of data and insights that makes it meaningful to leadership.

- Ensuring all key processes are done to highest standards such as Data Protection, inclusive user research practices, and ethic approval processes are all in place to enable speedy recruitment when we need to.

- Recruitment of participants can be challenging at times, so internal means of recruitment (as well as external) are very important. Those of us who work for universities are surrounded by options, so talk with other teams/departments, collaborate and find ways to attract and incentivise those you end up talking to!

- Showing our work via informal mechanisms such as show and tell sessions with the delivery teams. We also present and report our work more formally to stakeholders, so they can appreciate the wider perspective that is required to come up with a design.

- The big difference from my point of view is that all colleagues are invited to observe, or take notes in user research sessions. We’ve opened it to members of our community who have a stake in the projects we work on. This proved to be invaluable when stakeholders hear directly from an end user about the specific issues they encountered when trying to use a product on the website. It has not been unusual to hear university colleagues asking whether it would be possible to change something after they directly observe the issues. We’ve also opened up our research and design synthesis sessions with a clear process which our user researchers facilitate to help inform the designs. These help us to show our work and how we arrived at a particular design.

My tip here is it will always be better to show, rather than tell! Always involve others where you can and be clear how insights are communicated widely objectively.

Jared Spool describes it well when he says that “the most significant value that UX can bring to an organisation is to turn everyone into the world’s foremost experts in who their users are and what they need.

To pull that off, you’ll need to conduct research. Research that develops the expertise in who the users are and what the users need.”

For that you need a mindset shift – it needs buy-in, commitment, involvement of others because it is no longer just down to you to be an expert about your users.

Summary

I don’t want to paint the impression that I have all the answers. The reality is that this is a long journey that needs determination because there is always another bend in the road, or a mountain to overcome.

I would also acknowledge that it’s also hard to predict when (any) organisations might lose interest and their patience runs out when you invest time up front in investigating a problem. I get it. This is why you need to get the perceived value for user research, ResearchOps and any other discipline or practice to that effect, as quickly as possible. You also need to continue delivering results as a team to ensure you are renewing the faith of the organisation along the way. That can be hard because tangible impact is what matters most to the organisation.

To win an award was gratifying for all the work to be recognised, but I also acknowledge that there is a lot more to do. All that glitter is well-deserved, but it is not about perfection. This work simply helps us understand what is the actual problem we need to solve for our audiences and how we can do our minimal viable product right, first time round. That in itself brought efficiency, reduced costs longer-term, and brought a competitive advantage.

Understanding your audiences is also a moving target. Our audiences need us to keep up with their needs as they change. That takes commitment. It’s why iterations and continual learning about people is important. User needs shift and change over time, and we need to keep up with that. We have great examples of it and it does help when you take it back in front of the organisation.

From a leadership point of view, any implementation of disciplines, processes and frameworks has to be sustainable and embedded into organisational strategies. Don’t get me wrong – building a strong practice is great and I’m obviously a big advocate of it, but what the organisation buys is results. Showing how your team’s work helps the organisation achieve its aims is time well spent. Like it or not, organisations may never be interested in the practice, but it will always be interested in results.