In celebration of this year’s Global Accessibility Awareness Day (#GAAD), let’s take a look at some of the challenges in defining excellence in digital accessibility on an organisational level.

Defining accessibility

The word ‘accessibility’ gets used a lot. Since 23 September 2019 the law around website accessibility has changed for public sector organisations.

As a university, we’re lucky to have some very dedicated expert colleagues in different parts of the organisation. They range from world-leading researchers to service providers, and dedicated digital and user experience practitioners. We’re also lucky to have access to students and other users, including disabled students and other advocates. They all work very hard to push the accessibility and inclusivity as high as possible on the University’s agenda. I’m always grateful to be working at a place that values and tries to do the right thing by the user.

Over a number of years, I have had lots of conversations about accessibility. One observation that I’ve had is that people often have very different lenses on the topic and what ‘good’ means. That in itself can occasionally make having effective conversations and agreeing on shared definitions difficult.

The digital services definition

I’ve been looking at a lot of different definitions, tested accessibility design patterns and guidance. Often, the word ‘accessibility’ gets used to describe how many people can use something.

The Government Digital Services Guidance defines ‘accessibility’ as “more than putting things online. It means making your content and design clear and simple enough so that most people can use it without needing to adapt it, while supporting those who do need to adapt things”.

I like Lou Downe’s Good Services design principles, especially number #11: a good service is usable by everyone, equally. “The service must be used by everyone who needs to use it, regardless of their circumstances or abilities. No one should be able to use the service less than anyone else” (Good Services, Lou Downe). Lou makes a case for designing for inclusion, and this goes beyond accessibility.

Inclusion is a necessity, not an enhancement poster. Lou Downe, Good Services.

Inclusion is a necessity, not an enhancement poster. Lou Downe, Good Services.

Her point also helps set the scene a little for why it has been tricky for us as a programme, and for many other organisations, to be clear on what actually ‘gold’ (beyond the required minimum) accessibility standards are for our University.

So why is it so challenging? Here’s my non-exhaustive list:

Challenge 1: there’s no A to Z guide for applying accessibility

The OneWeb programme was set up specifically to re-engineer digital services and products for our many end-users. Essentially the brief is to design every service around user needs. Accessibility can obviously affect the needs of every group we design for so ‘baking in accessibility’ has always been one of the guiding principles of the programme.

If the goal is to meet users’ needs, then surely we must try to make our services as inclusive as possible. We’re doing this by ensuring there are no barriers that make it impossible or difficult for anyone to use them. We want our services to be easy to use by everyone.

This isn’t always simple though.

Stakeholders and end-users often have conflicting requirements and there will be situations that are overlooked due to us being unaware of them.

So it is important to understand why someone might be more likely to be excluded from our service and tackle the underlying causes for it. For example, providing an alternative way of contacting us, or ensuring we represent diversity in our imagery.

In reality though when deadlines are short, budget is limited, there are legacy systems at play, and other challenges to work with – compromises do happen. This is not something that I think we should accept lightly, but I’m being honest about it.

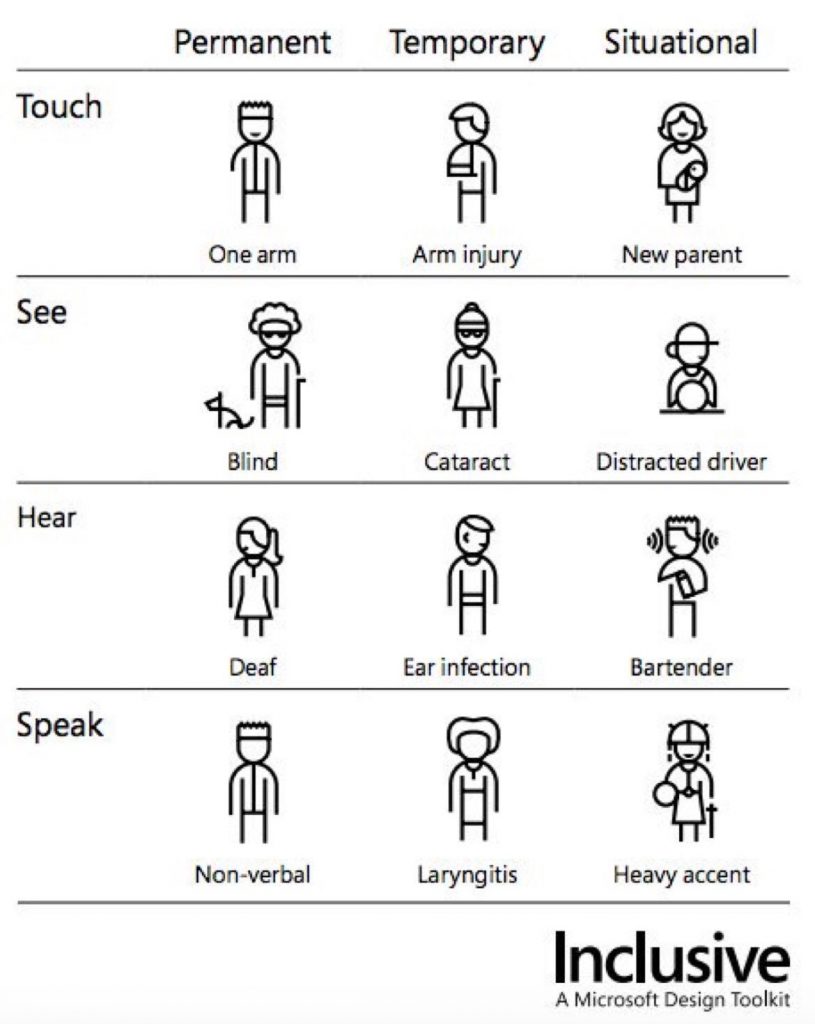

Also as we’ve already established, inclusivity goes way beyond digital services. We need to consider other touch-points in the journey including when individuals may have a temporary or a permanent access issue. It goes all the way to physical access in buildings to HR policies.

Microsoft Design Toolkit: Examples of permanent, temporary or situational impairment via @realHayman

Microsoft Design Toolkit: Examples of permanent, temporary or situational impairment via @realHayman

This is one of many reasons why diversity in teams and organisations is important. It’s why we must conduct regular user research with our audiences and test with as many users as possible to make sure our services truly work for everyone. It does beg the question – how much can you polish stuff that hasn’t been built with users in mind, let alone accessibility and inclusivity in mind?

This cannot be an after-thought. It has to be ‘baked-in’ right from the start to make sure our services are:

- useful

- usable

- desirable

- accessible

- credible

- findable

- valuable

- and inclusive

“Inclusion is like making blueberry muffins – it’s a lot easier to put the blueberries in at the start than in the end.” Cordelia McGee-Tubb (@cordeliadillon ) in Good Services, Lou Downe.

So really, good accessibility design – is just good human-centred design. It is about accommodating 100% of your potential users.

“We treat disabled people as if they are different but that isn’t the case, as digital accessibility affects all of us. If nothing else, you should see it in a selfish way, as one day you will probably need this type of accessibility.” Laura Kalbag.

Challenge 2: evolving guidelines

Given that we design digital services, we refer to the W3C (the body that produces many of the standards that the web relies on) Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG 2.1). There are three conformance levels:

- A,

- AA,

- AAA

‘A’ is the minimum level of accessibility. We aim as a minimum for AA level as a public sector institution.

Achieving ‘one best way’ for compliance with WCAG 2.1 can be challenging, fraught with complexity and might result in lack of clarity, which is time consuming and can be expensive when the clock is ticking on your project. In reality there could be different interpretations of accessibility standards, which can create natural tension between experts, such as content designers, user researchers, developers, UX designers, product owners and executives.

As far as I’m concerned, the standards were never intended to allow for multiple interpretations, but different interpretations serve different needs, and are not less or more valid than one another. As such, organisations should define the goals they are striving for, so that when designing, testing and auditing the work, everyone is working to the same interpretation. Easier said, than done – I know!

In terms of OneWeb, and eventually when the programme moves to Business-As-Usual, all new features we’ve shipped over the past year have been designed and tested to meet WCAG 2.1 AA guidelines to ensure our products are accessible.

At the same time, we’ve gone back and retrofitted existing features and interactions for better accessibility on live products. Examples of it will be changes to content following content design best practice from the Readability Guidelines – a universal content style guide, based on usability evidence. Other examples will be in development and prototyping of specific features such as navigation, forms and other components.

Challenge 3: stakeholders and strategies

This is probably one of the most challenging parts of all. In a large, complex organisation like a university that is inherently fragmented by its devolved nature, it can be difficult to find the right voice that can guide us with ease to the right strategy and outcomes.

The truth is that when accessibility is introduced as an organisation-wide practice, rather than just observed by a few people within specific teams, it will inevitably be more successful. If accessibility is the objective, inclusivity is surely the outcome. When everybody understands the importance of accessibility and the part they can play, we can make great (digital) services.

Accessibility is a right – not a privilege

Accessibility is a right – not a privilege

We’re aiming high, so if we’re to be bold and try to achieve a gold standard (uncharted territory for us right now) as an organisation, we need to define it for all areas, not just web accessibility. For the practice to succeed it cannot be seen just as a line item in the budget. It’s an underlying practice that affects every aspect of the physical and online services as an institution.

Striving for an ideal approach is also not always about meeting organisational needs as this may require additional funding. Not because accessible services are more expensive. Simply because it requires teams to be developed and trained, and because we have to ensure our users can use the service in the way that best suits them. That sometimes means providing alternative materials like translations, or transcripts to benefit all users.

And as standards evolve, what’s technically possible today, may be completely different in 12-months time (or even less) and therefore we should be thinking longer-term so we can optimise for advancements as they happen. For example, automated captioning for video has come a long way in the last 10 years.

Being transparent

From speaking with the finest minds about accessibility within our organisation and beyond, we’re still busy ‘baking it in’.

As a team, we’re still chasing the ultimate view of gold standards that we’re defining with our university. In the next few weeks, we’re hoping to start sharing with other colleagues some of our learning, the assets we’re currently developing such as improved reusable components and pattern libraries, and best practice content design examples. However, it takes time and practice – from inclusive user research, to product development, testing, and expertise, to consistently work at this level.

One thing’s for sure – the importance of a defined and accepted strategy is the first part of addressing the challenge of how we’re going to define, develop and meet a gold standard in accessibility and inclusivity.

Global Accessibility Awareness Day takes place on 21 May 2020. Thank you for reading.

My thanks to Mark Wyatt, Jonny Vaughan and Dr. Sarah Lewithwaite for their thoughts and suggestions on this post.

To sign up for further updates, please use this form.

Resources we learn from:

- Readability Guidelines from Content Design London

- Good Services by Lou Downe

- The World Wide Web Consortium

- World Accessibility Initiative

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1

- Digital accessibility Centre

- AbilityNet

- GOV.UK accessibility guidance

- Accessibility blog GOV.UK

- Accessibility for everyone by Laura Kalbag

- Microsoft inclusive design

- NHS accessibility guidance

- The great accessibility bake off by Cordelia McGee-Tubb