It’s personal

Hey. 👋 I’m Ayala and I’m a self-confessed optimist: I generally think that everything will work out just fine if you work hard and take calculated risks every now and again.

Those who know me well will tell you that conformity and patience have never been my greatest strengths.

I was brought up on a kibbutz: a collective community where, from a very young age, we were expected to be independent, self organise and contribute to the broader community needs (people over profit). It was safe and everyone played by the same rules. But it was also a real mixture of dynamics between collectivism and individualism, which created what I would call ‘positive tensions’. This idea has stayed with me and I still believe that the power of the group – harnessed properly – is awesome, and that doing so requires embracing short-term pain in favour of longer-term gains.

Image: ‘kibbutz life’ collective celebration. Source: Kibbutz archives

Image: ‘kibbutz life’ collective celebration. Source: Kibbutz archives

Collective vs self interest

This post is not about me, or the story of my life. It’s actually about ‘governance’ and how to make short-term changes stick and endure the stress test of real life. These are big ideas, and often big ideas make big organisations nervous. So to make lasting change requires quite a lot of optimism combined with more than a pinch of realism! Governance also requires us to get to the ‘sweet spot’ of the overarching power of the collective balanced with the proactive need of the individual.

For the past two years, I’ve been the Business Owner of OneWeb, a large-scale digital transformation programme at the University of Southampton. Working with many different functions and colleagues, I’ve noticed some strong parallels and that’s what ‘re-triggered’ some of this thinking.

So, after all of the hard work we’ve put in, and as we look to both conclude and look towards the future benefits of completing our ambitious programme, I wanted to share a few thoughts and learnings.

1# Governance isn’t a dirty word (but can be seen as evil)

Seventy percent of digital transformation efforts fail. And they normally fail for pretty consistent reasons. I’ve spoken a lot about the messiness of change and the messiness of humans, and my experience to date has confirmed what a difficult thing transformation within large organisations is to achieve.

The problem is that the word ‘governance’ is often mistaken for meaning ‘restrictions’: putting limitations in the way of individual needs and creativity. The power of the collective is much stronger than the individual, and in the context of a university (or any large, complex organisation), this often leads to some prioritisation of the ‘centre’ over the ‘individual’ (aka faculties, schools, academics).

Anyway, you get the idea. While individuals are mainly on board with everything you’re proposing, collectively, the narrative is such that people in the organisation dislike, even hate, any idea that this may mean they have to conform to the centre. On the other hand, governance (done well) is a force for good for everyone: the group, the organisation and the individual.

#2 Maintaining is as important as building

“Another flaw in the human character is that everybody wants to build and nobody wants to do maintenance.” – Kurt Vonnegut, Hocus Pocus.

I agree with Kurt. Governance is essential when you form digital services and it’s through ongoing maintenance and development that you capitalise on big investment.

When creating new and improved services for users, many organisations often don’t delve deep enough into the internal efforts within the collective that delivers that service. This is risky because it can bring a lot of confusion and uncertainty about ownership and responsibilities, funding models and other critical elements such as standards and ways of working. Standards, of course, help with re-use and maintenance.

When OneWeb got approved in 2019 we were adamant that we didn’t want to limit ourselves to just improvements that lie directly in the user interface. The mandate was to create a real change – create services and products that meet user needs – that would last beyond a facelift. Not just re-skinning, and legitimising new visuals, but doing it properly and getting to the root of the issues. This meant sorting out governance issues so we never have to do expensive ‘facelifts’ ever again.

That’s of course easier said than done. Service design, user research and journey mapping have all helped us to understand the bigger picture better since we’ve started. We collaborated with external users and our colleagues internally to understand what all services’ layers and interfaces are made of. We knew that we had to start somewhere, and the website was an obvious place to focus our initial change, but with all this work came a catch-22 scenario. We know that our users want a single, integrated experience. They are not interested in learning how to carefully navigate our various channels and systems just to understand what’s going on inside our organisation and their place within it.

So the questions become:

- how do we get our stakeholders to recognise that building new, shiny things is often (wrongly) prioritised over maintenance and re-use?

- how do we get others to recognise that the world is littered with abandoned innovations?

- how do we address governance in a way that benefits the organisation (i.e. not reverting back to type, allowing us to achieve outcomes that we never imagined before)?

- how do we make the processes and standards really clear whilst preserving a sense of creativity and individualism at the same time?

These are big questions – ones I am seeking to answer.

#3 There needs to be a big ‘G’ in Governance

Back to Kibbutz life.

Life in the community is unlike anything I’ve experienced before or since. There’s little privacy, the sheer number of people coming and going is difficult to adapt to, and having company at all times forces you to regularly confront your personal flaws. Communal often means secure, it means creative, it means diverse, it means open to debate. It also means new, diverse connections, which is one of the biggest challenges of governance – collaborating with others.

My point is – to do a proper job of digital services, and to manage the user experience properly, and to stop buying things we do not need, governance must underpin all the following service layers:

- user interface

- collaboration within the organisation

- nasty IT / legacy stuff

- data and information design

Governance is also a major enabler for digital.

We should all learn from past experiences. Organisations tend to do what’s easiest for a particular department, faculty, or even a manager. I know it sounds harsh, but how do we stop and ask ourselves:

- who is accountable for good or bad design?

- who is accountable for good / bad information?

- who is accountable for the impact it creates for the user?

Good governance should be supportive.

If you haven’t thought of it properly you will have a challenge on your hands. A focus on services is now more important than ever because they’re our engines: for data, for design, for systems. And governance is a major enabler for digital as well as communities of practice to flourish because good ‘big governance’ should be the glue that enables small-scale flexibility and excellence..

#4 Unless culture changes, we will be running uphill with one arm tied behind our backs

Culture is always an interesting component and I have difficulty describing it. As per Simon Wardley:

“… you can’t change the culture by diktat, it’s a function of the experience of the people. If you want to change the culture you have to change the experience of those people.”

So unless we make some fundamental changes in how we come together, communicate and organise ourselves, we will continue to feel as if we’re running uphill with one (or two) arms tied behind our back. And damn – that makes things harder than they should be!

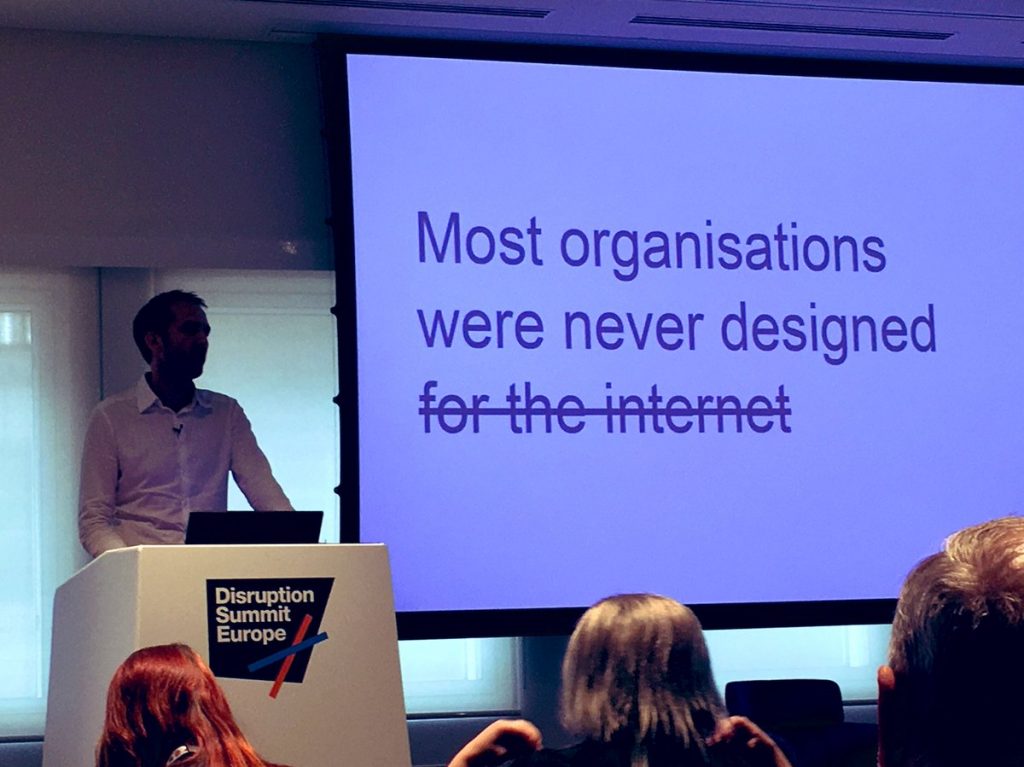

Image: Most organisations were never designed (for the internet), Source: Twitter, Disruption Summit

Image: Most organisations were never designed (for the internet), Source: Twitter, Disruption Summit

Kibbutz life offered stability, identity, community, belonging, a world view that previous generations to mine had lost. My kibbutz was a powerhouse when it came to agriculture and technology in its very heyday. People were ambitious together. But it failed to anticipate a ‘second day’ revolution, in which many among my generation sought new adventures elsewhere. It also failed to anticipate the messiness human beings desire, and how it can, in a closed, family-like system, produce uniquely poisonous variants of hurt and betrayal. Collective memory (or as I call it ‘the broken hearts club’💔) can lead to a long period of collective soul-searching and problem solving running up hill…

Can you see the parallels, or have I digressed? 😉

But there are some strong lessons here for governance.

My kibbutz did eventually turn itself around: from a close and rigid, risk-averse culture to a dramatically more diverse and inclusive culture with a lot more freedom for people to operate within the community’s parameters (framework), where everybody shares spaces, communal social and cultural life, and major decisions…

So a few more thoughts on how we could potentially overcome some challenges, some heavily influenced by speaking with my team members as well as Lou Downe’s book ‘Good Services’, which I will attempt to summarise below.

Not channels, services:

We don’t solve users’ problems by building a thing and sticking it on a website. Fast forward a few years, and the complaints about the website from everyone in the organisation will become unbearable:

- nobody can find their way around the website

- student-facing services are bogged down with questions from confused students

- product owners are frustrated with users who can’t make sense of their services or products

Then finally, someone decides that something has to be done. We really need to change the conversation. We should be talking about journeys and experiences for users, which make up a service.

With my team, we sometimes talk about and organise ourselves around areas like ‘courses’ or ‘education’. But really what we’re talking about is ‘Becoming an undergraduate student’, or ‘finding people and expertise’. These are all services. If we look at it end-to-end it includes multiple touchpoints, both digital and physical, some of which start long before people are aware of us.

Action:

- we need to define what a ‘service’ is at UoS and look at them end-to-end.

Image: Good services are designed. Credit: Lou Downe, Good services

Image: Good services are designed. Credit: Lou Downe, Good services

Organise ourselves around services:

Not at all easy to do in large complex organisations with plenty of egos, but if we set up teams and jobs around services, this affects interaction with stakeholders as well as team dynamics. The risk is that if you ignore it, you’re creating silos and disjointed experiences.

Take for example data design – by building data infrastructure that ignores the drivers that shape the environments in which the infrastructure is deployed and built, this will ultimately result in brittle infrastructure. Funding choices shape the type of infrastructure we get.

Funding choices > poor infrastructure + poor data design = poor user experience = (poor services).

Action:

- to align ourselves to services with some joined KPIs and not some lower level / vanity metrics.

- to get under the skin of our corporate strategy so we can create a funding model that can support a future digital infrastructure (with designers, technologists and information builders).

Cut across in another way:

However teams organise, there’s always a tendency to work in silos. Cutting across departments helps to build more collaborative functions into job roles e.g. lead roles that look across a set of services for certain types of users. Design crits and similar meetings also help to expose what teams are working on and build consistency of approach.

Action:

- to change structure, and processes to align against a service model.

- to look at artefacts, such as common journeys, data standards, architecture, diagrams, design and content patterns, dashboards to ensure everyone has a shared understanding.

#5 Conclusions: world of imperfection

We buy systems instead of processes, capabilities and skills. The bottom line is that services have evolved and now behave in a way that just about makes ends meet. They’ve evolved to work in a particular way, but now they’ve reached such a point where everything is frozen in time.

This is because when people (customers) keep paying for the service, it’s hard to make the case for change. And few people are incentivised to make the case for change because livelihoods depend on everything staying just the way it is.

But our customers don’t ask for backend process improvements. They don’t ask for efficient devOps, or design systems, or product teams. They want what those things enable, but they are not going to mandate how we do what we do.

The hardest challenge is to sometimes accept that companies and organisations often do what is worst for them. We must persevere and keep showing that there is huge value in improving skills and processes, in focusing on quality, not quantity.

What we started as part of OneWeb lets our organisation deliver on these benefits. We haven’t arrived in my utopian state – for that, we also need good governance.

The double-irony is that everything I’ve mentioned – improving processes, standards etc. – also helps the ‘sexy’ stuff with AI and dashboards that management is keen on and might even pay for (but might not actually need to).

And no system on its own can do anything useful. Data and information quality is one of the huge challenges today; a tremendously complex problem that requires highly skilled people and well designed systems. But so few organisations want to invest in the skills and think big. And decision-making around what our teams (and others) are making has to be cut and clear.

Image: Leading transformational change. Source: Torben Rick

Image: Leading transformational change. Source: Torben Rick

Everyone in the teams needs to understand where we’re heading, and people outside the teams need to know our strategy so they can see how it helps the University and how they can help if they have the information we need.

Bringing it back the full-circle: let’s understand what we’re doing and what is the role of governance in the creation of services, and how we’re going to do it consistently. If we can reach a state of ‘positive tension’ – where seemingly conflicting views unite under the banner of good governance – then individuals can decide if they are going to collaborate, or leave the pack. Just like in a collective.

At the end of the day, we all live in a large globalised digital kibbutz and our survival depends on our communal skills, not just trust in our leaders.

Intent matters: it’s not what you believe in – it’s what you do. Source: Kibbutz archives

Intent matters: it’s not what you believe in – it’s what you do. Source: Kibbutz archives

Thank you for reading my post to the end. We’re looking at developing our governance approach and principles, so please come back in 2021 to check on our progress and updates.

My immense thanks to Mark, Jonny, Kate, Andy, Dan for their thoughts, contribution and suggestions. Thoughts and comments are always welcome, especially If you have managed to make short-term changes stick, I would love to hear from you.

To sign up for further updates, please use this form.